Friday, June 27, 2008

Falcons are really Parrots?

A new study published this week in the journal Science reveals some surprising previously unknown facts about the bird family tree--such as that falcons might actually be more closely related to parrots than to hawks. And that parrots, falcons, and songbirds are all more closely related to each other than to any other birds. Go figure! And it looks like hummingbirds and swifts evolved from nocturnal nightjars. Its going to take a while to confirm these results and to sort it all out, but there are going to be changes to how we view bird evolution, that's for sure. At any rate, you can read a summary here.

Thursday, June 26, 2008

Join the Birdchaser in Maine

I'm heading up to Maine this weekend with my family to help with the Family Birding Adventure at the Hog Island Audubon Camp. If work's getting you down, they can probably still make room for a couple more people up there next week.

I'm heading up to Maine this weekend with my family to help with the Family Birding Adventure at the Hog Island Audubon Camp. If work's getting you down, they can probably still make room for a couple more people up there next week.I'll be back on Hog Island in August for the Audubon Chapter Leadership week (scroll through some of my past exploits up there in 2005, 2006, and 2007). If you are a chapter board member or committee chair, come on up and spend the week with us to learn more about how to use National Audubon programs and tools to help your chapter. If you aren't a member of an Audubon chapter, or a chapter leader, then the questions is why not? Birds and the environment need all the help they can get! If hanging out on an island in Maine and seeing breeding Atlantic Puffins isn't enough of an inducement, I don't know what else is!

Come on up to Maine, enjoy the soul and body satisfying setting and programs at Hog Island.

Tuesday, June 24, 2008

Bird Atlasing

This is the last year of the Pennsylvania Breeding Bird Atlas project, and I still have a lot of holes in my assigned survey block, so yesterday I spent a few hours in the morning driving the roads around Souderton and Franconia, in Montgomery County. No real surprises, but I was able to confirm breeding for a few more species, and find possible breeding Eastern Kingbirds in two places. Its fun to do these surveys, and to spend a little more time watching each bird to see what their behavior will tell you about their breeding status. With a few extra minutes of watching, that Chipping Sparrow goes from just a probable breeder, to confirmed as it flies over and feeds a fledged young bird. Very fun.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

The Daily List

At 7:30 this evening I was sitting at home when I realized I hadn't gotten my Bird RDA, so I quickly slipped down to the creek and park behind my house. In less than 20 minutes I pushed the day list to 22 species, only 110% of the Bird RDA, but better than nothin!

1) Blue Jay

2) Fish Crow

3) Mallard

4) Great Blue Heron

5) Chimney Swift

6) Barn Swallow (seen on way to church in the morning)

7) Common Grackle

8) Mourning Dove

9) European Starling

10) House Sparrow

11) Song Sparrow

12) House Finch

13) Carolina Wren

14) House Wren

15) Eastern Bluebird

16) Carolina Chickadee

17) Gray Catbird

18) Northern Mockingbird

19) American Robin

20) American Goldfinch

21) Red-bellied Woodpecker

22) Northern Cardinal

1) Blue Jay

2) Fish Crow

3) Mallard

4) Great Blue Heron

5) Chimney Swift

6) Barn Swallow (seen on way to church in the morning)

7) Common Grackle

8) Mourning Dove

9) European Starling

10) House Sparrow

11) Song Sparrow

12) House Finch

13) Carolina Wren

14) House Wren

15) Eastern Bluebird

16) Carolina Chickadee

17) Gray Catbird

18) Northern Mockingbird

19) American Robin

20) American Goldfinch

21) Red-bellied Woodpecker

22) Northern Cardinal

Saturday, June 21, 2008

I started birding before I was born

As I've looked back on it, I think I started birding in the 40s or 50s, though I wasn't actually born until just after the Summer of Love. How's that? Because the books I had, the most important sources of information for my early ornithological explorations, all came from previous decades. Maybe I'm exaggerating a little. But only a little. Here are the three most important books for my early birding life, taken from the local public library:

Birds of Oregon (1940), I.N. Gabrielson and S. G. Jewett.

A Guide to Birdwatching (1943), Joseph Hickey

(Golden Guide) Birds of North America (1966), Chan Robbins

As a kid in the early 80s, these were the most important books I had. I remember feeling the thrill of finding Brown Pelicans on the Oregon Coast a few days earlier than the earliest date listed by Gabrielson and Jewett. I tried to take field notes as instructed by Joe Hickey. And of course my field identifications all came from using the Golden Guide.

So maybe I'm exaggerating slightly to say I started in the 40s. But in the early 1980s, before I hooked up with the local rare bird alert and other serious birders, I was still birding in the 40s. Or at the very latest in 1966, a couple years before I was born!

Birds of Oregon (1940), I.N. Gabrielson and S. G. Jewett.

A Guide to Birdwatching (1943), Joseph Hickey

(Golden Guide) Birds of North America (1966), Chan Robbins

As a kid in the early 80s, these were the most important books I had. I remember feeling the thrill of finding Brown Pelicans on the Oregon Coast a few days earlier than the earliest date listed by Gabrielson and Jewett. I tried to take field notes as instructed by Joe Hickey. And of course my field identifications all came from using the Golden Guide.

So maybe I'm exaggerating slightly to say I started in the 40s. But in the early 1980s, before I hooked up with the local rare bird alert and other serious birders, I was still birding in the 40s. Or at the very latest in 1966, a couple years before I was born!

Friday, June 20, 2008

Evolution of the Bird Photo Field Guide

I remember the first bird field guide I ever saw, it was the Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Western Region, by John L. Bull, John Farrand Jr., and the National Audubon Society. It had just come out and a neighbor had it when I was just a kid. I liked all the photos, but didn't actually use it as a field guide, since I was still just a casual birdwatcher (and more enthusiastic herper).

Photo guides have come a long way since those days, but there are still lots of questions about the limitations of a photo field guide to birds. To examine those, lets take a look back through time.

1977 Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region (John L. Bull, John Farrand, National Audubon Society).

This was pretty much the first photo guide, and the companion to the red-covered Western version I first saw. The vinyl cover made it waterproof and seem pretty rugged. That was nice. The photos were supposed to be arranged by similarity--both by shape (here we have some shorebirds) and by color--so if you thumbed back a bit farther you would get goldfinch and warbler photos close to each other, since they are both yellow. There was usually just one photo per species. All the photos were together at the front of the book, with all of the text in the latter part of the book. The text was actually pretty good, with lots of stuff about habits and habitat. It was mass produced, and the latest edition is still in print.

In the pre-National Geographic field guide era (up to 1983), this guide was one of the big three (along with Peterson's and the Golden Guide) popular bird guides. Lots of folks were attracted by the photos, and then were probably stuck with an attractive book that probably wasn't as easy to use to actually identify birds as were the other two books--which showed more species closer together and in more plumages.

Truth be told, I never bought a copy of these guides, even though you can find them at garage sales for almost nothing. I should probably pick one up for historical reasons next time I see one at the thrift store, but I've never bothered. In the early 1980s I thought this was the least useful of the major three guides, and now there are many more comprehensive and useful photo guides.

1983 The Audubon Society Master Guide to Birding, edited by John Farrand, Jr.

These three volumes were the first must-have photo guides. In order to compete in the serious bird guide market with the National Geographic Guide, these three volumes really were must-have books when they first came out. As the original tag line sold it, these guides covered

The guide featured text and photos (some paintings) on opposite pages, with tons of info geared towards field identification--most especially the detailed description and similar species sections. While in three volumes, it wasn't designed to be carried into the field, it did serve as a valuable identification aid and reference for checking up on bird identifications back home, or to bone up for birding trips. In my view, the best photo guides have been along these lines--specialized books not to be taken into the field, but to serve as identification resources back home--eg. The Shorebird Guide, Hawks from Every Angle, etc.

1988 An Audubon Handbook Eastern Birds, by John Farrand, Jr.

One more attempt to make a decent photo guide by John Farrand and Audubon, this vinyl covered book had a similar size and feel to the earlier Audubon guides, but now featured photos and text on the same page. The number of photos was still limited--though most species featured more than one photo, for a total of 1,354 photos of just over 460 species.

There was actually a lot of good to be said for this book, with each species getting its own page--even such rarities as Brown Jay. The photos were mostly pretty good, and there was much more text for each species than found in many recent guides--including a similar species section, which is most helpful for birders trying to make sure they aren't examining all their options when identifying a bird.

I never bought this book when it came out (I was in South America for a couple years), but the more I look at it now, the more I like it. But it does suffer from the biggest complaint about photo ID books--they only show individual birds, while an artist's illustration may be able to show a more standardized or representative view of a bird's plumage, posture, etc. Photo guides also suffer because the individual photos may be taken under very different lighting conditions, making it tough to really compare one photo with another--which can occasionally lead to errors in identification when color artifacts in the photos are used as field marks.

1996 Stokes Field Guide to Birds, Eastern Region, by Donald & Lillian Stokes

This is another book I passed on when it first came out, mostly due to the limitations in format. Similar to the Farrand handbook, this one has one species per page--which is generous when it comes to text, but with most species only getting one photo. The photos are pretty good, some are even stunning. There is no similar species section, but many notes on how to distinguish from most similar species are emphasized (in bold--a bit distracting at least for me) in the identification section of the text.

This is another book I passed on when it first came out, mostly due to the limitations in format. Similar to the Farrand handbook, this one has one species per page--which is generous when it comes to text, but with most species only getting one photo. The photos are pretty good, some are even stunning. There is no similar species section, but many notes on how to distinguish from most similar species are emphasized (in bold--a bit distracting at least for me) in the identification section of the text.

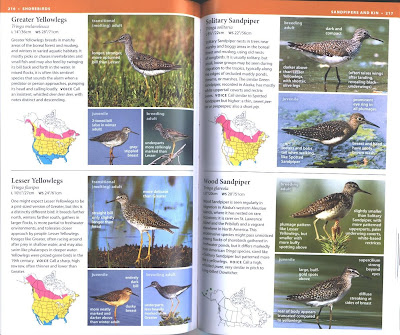

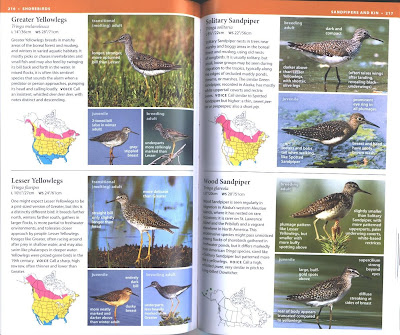

Again, with photos you don't have enough room to show all the plumages, so that's the biggest limitation. But even then, sometimes a reader is left to wonder why only one photo for a species like Wild Turkey (showing a pretty rangy looking hen), when many other sexually dimorphic birds get photos of both male and female birds? Of course, for beginners, you have to wonder how many plumages they really need to see. So it becomes a question of audience. For beginners, a field guide really needs to walk them through how to identify every bird--so you need good similar species discussions and other helpful tools, like comparison images. The Learning Pages for each bird family, easily found with colored tabs tied to a quick index inside the front and back cover, really helped here. But in a photo field guide organized with one species per page, you often don't even get the most similar species on facing pages, as in this case with Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs on separate page layouts.

So, photos are just mostly OK here, but the text is pretty good and lots of good info, helpfully broken into sections. As an aside, when it came out it was good to see conservation emphasized, if somewhat cryptically, in its own section per species.

2000 Kaufman Focus Guide, Birds of North America, Kenn Kaufman

While technically a photo guide, since it uses digitally enhanced photographic images of each species, this really is more of a traditional guide, in many ways similar in format to the old Golden Guide, which was a favorite of many for packing a ton of info into its tight format. In this case, Kenn Kaufman was able to avoid perhaps one of the biggest problems with photo guides--the "bulkiness" of the photos. While booksellers may laud the virtues of a bird being shown in its natural habitat, in reality, most bird photos only end up showing empty sky, water, leaves, or other unhelpful background, rather than useful habitat info. In addition, all that water or leaves take up so much room that its hard to get more images in of birds in additional plumages, poses, etc. While an artist can pack many images of a species into a tight space, photo guides are usually limited by the blocky rectangles of photos.

While technically a photo guide, since it uses digitally enhanced photographic images of each species, this really is more of a traditional guide, in many ways similar in format to the old Golden Guide, which was a favorite of many for packing a ton of info into its tight format. In this case, Kenn Kaufman was able to avoid perhaps one of the biggest problems with photo guides--the "bulkiness" of the photos. While booksellers may laud the virtues of a bird being shown in its natural habitat, in reality, most bird photos only end up showing empty sky, water, leaves, or other unhelpful background, rather than useful habitat info. In addition, all that water or leaves take up so much room that its hard to get more images in of birds in additional plumages, poses, etc. While an artist can pack many images of a species into a tight space, photo guides are usually limited by the blocky rectangles of photos.

Kenn Kaufman fixed that by just digitally taking the backgrounds out and photoshoping all the images into nice groups.

This isn't the place for a full review of this book, which I still consider probably the best field guide for beginners, but it is good to note that even though the text is spare, similar species are usually shown closely together, arrows point out field marks (though you usually have to supply your own discussion of those marks by comparing arrows on the photos), and there are usually more images per species than in previous photo guides (eg. two Philadelphia Vireo shots, as compared to just one in the Farrand and Stokes guides, and four vs. three shots of Least Tern).

Enter the latest 21st century photo bird guides, out within the last year...

2007 National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America, by Edward S. Brinkley

This isn't the place for a full review (look for that here soon!), but here's a quick first look. This book claims 2,100 photos of over 750 species. That's a lot of birds, and a lot of photos. Most birds get half a page, and all the text, maps, and photos have to be crammed into there. In order to do this, all the text on identification is superimposed on the photos, making it pretty spare. Whereas some of the older photo guides emphasized text more than photos, this guide is really stripped down. No similar species section here!

This isn't the place for a full review (look for that here soon!), but here's a quick first look. This book claims 2,100 photos of over 750 species. That's a lot of birds, and a lot of photos. Most birds get half a page, and all the text, maps, and photos have to be crammed into there. In order to do this, all the text on identification is superimposed on the photos, making it pretty spare. Whereas some of the older photo guides emphasized text more than photos, this guide is really stripped down. No similar species section here!

What you do get are some decent (some are even stunning) photos of each bird, including some that aren't covered in some of the more popular guides. Can't find Wood Sandpiper in your Sibley? Well here's a couple photos. Many other rarities are also featured. Editorially, again sometimes the reader is left scratching his or her head--while I'm tickled to see a photo of a baby American Oystercatcher, how useful is that shot in a field guide? Especially when other chicks aren't featured? Show me a whole plate of baby shorebirds, then I'd be happy (and really impressed, ever try to find photos of a baby Long-billed Curlew online?)!

2008 Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America, by Ted Floyd

Again, not the place for a full review (see that here later!), but here's a first look at this guide, which takes both a similar and yet different approach than the NWF guide. The layout of this guide is very attractive, with a half page (either vertical, or sometimes horizontal) dedicated to most species. As with the NWF guide, identification text is attached to each photo, but here as a caption rather than superimposed on the image.

Again, not the place for a full review (see that here later!), but here's a first look at this guide, which takes both a similar and yet different approach than the NWF guide. The layout of this guide is very attractive, with a half page (either vertical, or sometimes horizontal) dedicated to most species. As with the NWF guide, identification text is attached to each photo, but here as a caption rather than superimposed on the image.

In a guide dedicated to showing "the natural variation within and among species", the space-limiting nature of photo guides seems to be a big problem. Whereas other field guides show lots of images of Glaucous-winged Gull, how useful is this treatment where we only get one image of an adult (in flight) and the other two images in the species account are of standing adult and immature hybrid Western X Glaucous-winged Gulls? No doubt its fun to look at photos of hybird gulls (if you are into that kind of thing), but again, who is this guide for? Maybe this isn't the best example, because average birders may not even attempt to identify Glaucous-winged Gulls. But having grown up birding in Oregon, even as a newer birder, not having more images of this species would have been a big bummer for me.

There'll be time for more in depth coverage of this guide in the full review. For now, these last two books seem to highlight a couple of funny places we seem to be in as consumers of bird identification materials.

Ubiquitous bird photos: While its tough (and darn expensive) to come up with great color illustrations of birds, amazing digital bird photos are everywhere now. That makes coming up with a photo guide easier than ever before. And the later books have many more and better images than ever before. However, in the day when a Google image search can bring up dozens of shots of most bird species, what is the place for a photo guide? With the space limitations imposed by the photos, and for the other limitations noted above, it makes it tough for these books to function as well as a field guides. As a reference back home, its getting tougher to beat the Internet.

Audience: What is the audience for field guides? Advanced birders, who usually don't need them in the field, but may use them as reference materials at home? Again, why do they need a book, rather than the Internet? What about beginners? What type of info do they really need, and how can it be best presented in a field guide? I have a lot of admiration for all of the books I've featured here (even the old green and red vinyl Audubon guides had their moments), but for beginners, I'm not sure we've hit on the best recipe for a field guide, and I'm not convinced that traditional photo guides are going to be their biggest aid.

Its an exciting time, with more resources available than ever before. Photo guides will always have their place, but it remains to be seen (through sales, and use) exactly what that place will be as we move further into the 21st Century. I hesitate to even guess what that place might look like five, ten, or more years down the road!

Photo guides have come a long way since those days, but there are still lots of questions about the limitations of a photo field guide to birds. To examine those, lets take a look back through time.

1977 Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region (John L. Bull, John Farrand, National Audubon Society).

This was pretty much the first photo guide, and the companion to the red-covered Western version I first saw. The vinyl cover made it waterproof and seem pretty rugged. That was nice. The photos were supposed to be arranged by similarity--both by shape (here we have some shorebirds) and by color--so if you thumbed back a bit farther you would get goldfinch and warbler photos close to each other, since they are both yellow. There was usually just one photo per species. All the photos were together at the front of the book, with all of the text in the latter part of the book. The text was actually pretty good, with lots of stuff about habits and habitat. It was mass produced, and the latest edition is still in print.

In the pre-National Geographic field guide era (up to 1983), this guide was one of the big three (along with Peterson's and the Golden Guide) popular bird guides. Lots of folks were attracted by the photos, and then were probably stuck with an attractive book that probably wasn't as easy to use to actually identify birds as were the other two books--which showed more species closer together and in more plumages.

Truth be told, I never bought a copy of these guides, even though you can find them at garage sales for almost nothing. I should probably pick one up for historical reasons next time I see one at the thrift store, but I've never bothered. In the early 1980s I thought this was the least useful of the major three guides, and now there are many more comprehensive and useful photo guides.

1983 The Audubon Society Master Guide to Birding, edited by John Farrand, Jr.

These three volumes were the first must-have photo guides. In order to compete in the serious bird guide market with the National Geographic Guide, these three volumes really were must-have books when they first came out. As the original tag line sold it, these guides covered

"all 835 species of birds recorded on the continent, including 116 accidentals, this is the first field guide to North American birds specifically designed to satisfy the interests of the serious birder. Its three volumes contain, in all, 1245 full-color photographs, 193 paintings, 422 drawings, and 650 range maps, while 61 of the nation’s top field ornithologists and experts contribute their special knowledge to the 370,000 words of text. Entries are arranged taxonomically to the new American Ornithologist’s Union Classification"

The guide featured text and photos (some paintings) on opposite pages, with tons of info geared towards field identification--most especially the detailed description and similar species sections. While in three volumes, it wasn't designed to be carried into the field, it did serve as a valuable identification aid and reference for checking up on bird identifications back home, or to bone up for birding trips. In my view, the best photo guides have been along these lines--specialized books not to be taken into the field, but to serve as identification resources back home--eg. The Shorebird Guide, Hawks from Every Angle, etc.

1988 An Audubon Handbook Eastern Birds, by John Farrand, Jr.

One more attempt to make a decent photo guide by John Farrand and Audubon, this vinyl covered book had a similar size and feel to the earlier Audubon guides, but now featured photos and text on the same page. The number of photos was still limited--though most species featured more than one photo, for a total of 1,354 photos of just over 460 species.

There was actually a lot of good to be said for this book, with each species getting its own page--even such rarities as Brown Jay. The photos were mostly pretty good, and there was much more text for each species than found in many recent guides--including a similar species section, which is most helpful for birders trying to make sure they aren't examining all their options when identifying a bird.

I never bought this book when it came out (I was in South America for a couple years), but the more I look at it now, the more I like it. But it does suffer from the biggest complaint about photo ID books--they only show individual birds, while an artist's illustration may be able to show a more standardized or representative view of a bird's plumage, posture, etc. Photo guides also suffer because the individual photos may be taken under very different lighting conditions, making it tough to really compare one photo with another--which can occasionally lead to errors in identification when color artifacts in the photos are used as field marks.

1996 Stokes Field Guide to Birds, Eastern Region, by Donald & Lillian Stokes

This is another book I passed on when it first came out, mostly due to the limitations in format. Similar to the Farrand handbook, this one has one species per page--which is generous when it comes to text, but with most species only getting one photo. The photos are pretty good, some are even stunning. There is no similar species section, but many notes on how to distinguish from most similar species are emphasized (in bold--a bit distracting at least for me) in the identification section of the text.

This is another book I passed on when it first came out, mostly due to the limitations in format. Similar to the Farrand handbook, this one has one species per page--which is generous when it comes to text, but with most species only getting one photo. The photos are pretty good, some are even stunning. There is no similar species section, but many notes on how to distinguish from most similar species are emphasized (in bold--a bit distracting at least for me) in the identification section of the text.

Again, with photos you don't have enough room to show all the plumages, so that's the biggest limitation. But even then, sometimes a reader is left to wonder why only one photo for a species like Wild Turkey (showing a pretty rangy looking hen), when many other sexually dimorphic birds get photos of both male and female birds? Of course, for beginners, you have to wonder how many plumages they really need to see. So it becomes a question of audience. For beginners, a field guide really needs to walk them through how to identify every bird--so you need good similar species discussions and other helpful tools, like comparison images. The Learning Pages for each bird family, easily found with colored tabs tied to a quick index inside the front and back cover, really helped here. But in a photo field guide organized with one species per page, you often don't even get the most similar species on facing pages, as in this case with Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs on separate page layouts.

So, photos are just mostly OK here, but the text is pretty good and lots of good info, helpfully broken into sections. As an aside, when it came out it was good to see conservation emphasized, if somewhat cryptically, in its own section per species.

2000 Kaufman Focus Guide, Birds of North America, Kenn Kaufman

While technically a photo guide, since it uses digitally enhanced photographic images of each species, this really is more of a traditional guide, in many ways similar in format to the old Golden Guide, which was a favorite of many for packing a ton of info into its tight format. In this case, Kenn Kaufman was able to avoid perhaps one of the biggest problems with photo guides--the "bulkiness" of the photos. While booksellers may laud the virtues of a bird being shown in its natural habitat, in reality, most bird photos only end up showing empty sky, water, leaves, or other unhelpful background, rather than useful habitat info. In addition, all that water or leaves take up so much room that its hard to get more images in of birds in additional plumages, poses, etc. While an artist can pack many images of a species into a tight space, photo guides are usually limited by the blocky rectangles of photos.

While technically a photo guide, since it uses digitally enhanced photographic images of each species, this really is more of a traditional guide, in many ways similar in format to the old Golden Guide, which was a favorite of many for packing a ton of info into its tight format. In this case, Kenn Kaufman was able to avoid perhaps one of the biggest problems with photo guides--the "bulkiness" of the photos. While booksellers may laud the virtues of a bird being shown in its natural habitat, in reality, most bird photos only end up showing empty sky, water, leaves, or other unhelpful background, rather than useful habitat info. In addition, all that water or leaves take up so much room that its hard to get more images in of birds in additional plumages, poses, etc. While an artist can pack many images of a species into a tight space, photo guides are usually limited by the blocky rectangles of photos.Kenn Kaufman fixed that by just digitally taking the backgrounds out and photoshoping all the images into nice groups.

This isn't the place for a full review of this book, which I still consider probably the best field guide for beginners, but it is good to note that even though the text is spare, similar species are usually shown closely together, arrows point out field marks (though you usually have to supply your own discussion of those marks by comparing arrows on the photos), and there are usually more images per species than in previous photo guides (eg. two Philadelphia Vireo shots, as compared to just one in the Farrand and Stokes guides, and four vs. three shots of Least Tern).

Enter the latest 21st century photo bird guides, out within the last year...

2007 National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America, by Edward S. Brinkley

This isn't the place for a full review (look for that here soon!), but here's a quick first look. This book claims 2,100 photos of over 750 species. That's a lot of birds, and a lot of photos. Most birds get half a page, and all the text, maps, and photos have to be crammed into there. In order to do this, all the text on identification is superimposed on the photos, making it pretty spare. Whereas some of the older photo guides emphasized text more than photos, this guide is really stripped down. No similar species section here!

This isn't the place for a full review (look for that here soon!), but here's a quick first look. This book claims 2,100 photos of over 750 species. That's a lot of birds, and a lot of photos. Most birds get half a page, and all the text, maps, and photos have to be crammed into there. In order to do this, all the text on identification is superimposed on the photos, making it pretty spare. Whereas some of the older photo guides emphasized text more than photos, this guide is really stripped down. No similar species section here!

What you do get are some decent (some are even stunning) photos of each bird, including some that aren't covered in some of the more popular guides. Can't find Wood Sandpiper in your Sibley? Well here's a couple photos. Many other rarities are also featured. Editorially, again sometimes the reader is left scratching his or her head--while I'm tickled to see a photo of a baby American Oystercatcher, how useful is that shot in a field guide? Especially when other chicks aren't featured? Show me a whole plate of baby shorebirds, then I'd be happy (and really impressed, ever try to find photos of a baby Long-billed Curlew online?)!

2008 Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America, by Ted Floyd

Again, not the place for a full review (see that here later!), but here's a first look at this guide, which takes both a similar and yet different approach than the NWF guide. The layout of this guide is very attractive, with a half page (either vertical, or sometimes horizontal) dedicated to most species. As with the NWF guide, identification text is attached to each photo, but here as a caption rather than superimposed on the image.

Again, not the place for a full review (see that here later!), but here's a first look at this guide, which takes both a similar and yet different approach than the NWF guide. The layout of this guide is very attractive, with a half page (either vertical, or sometimes horizontal) dedicated to most species. As with the NWF guide, identification text is attached to each photo, but here as a caption rather than superimposed on the image.

In a guide dedicated to showing "the natural variation within and among species", the space-limiting nature of photo guides seems to be a big problem. Whereas other field guides show lots of images of Glaucous-winged Gull, how useful is this treatment where we only get one image of an adult (in flight) and the other two images in the species account are of standing adult and immature hybrid Western X Glaucous-winged Gulls? No doubt its fun to look at photos of hybird gulls (if you are into that kind of thing), but again, who is this guide for? Maybe this isn't the best example, because average birders may not even attempt to identify Glaucous-winged Gulls. But having grown up birding in Oregon, even as a newer birder, not having more images of this species would have been a big bummer for me.

There'll be time for more in depth coverage of this guide in the full review. For now, these last two books seem to highlight a couple of funny places we seem to be in as consumers of bird identification materials.

Ubiquitous bird photos: While its tough (and darn expensive) to come up with great color illustrations of birds, amazing digital bird photos are everywhere now. That makes coming up with a photo guide easier than ever before. And the later books have many more and better images than ever before. However, in the day when a Google image search can bring up dozens of shots of most bird species, what is the place for a photo guide? With the space limitations imposed by the photos, and for the other limitations noted above, it makes it tough for these books to function as well as a field guides. As a reference back home, its getting tougher to beat the Internet.

Audience: What is the audience for field guides? Advanced birders, who usually don't need them in the field, but may use them as reference materials at home? Again, why do they need a book, rather than the Internet? What about beginners? What type of info do they really need, and how can it be best presented in a field guide? I have a lot of admiration for all of the books I've featured here (even the old green and red vinyl Audubon guides had their moments), but for beginners, I'm not sure we've hit on the best recipe for a field guide, and I'm not convinced that traditional photo guides are going to be their biggest aid.

Its an exciting time, with more resources available than ever before. Photo guides will always have their place, but it remains to be seen (through sales, and use) exactly what that place will be as we move further into the 21st Century. I hesitate to even guess what that place might look like five, ten, or more years down the road!

Monday, June 16, 2008

Survived!

Just over a month ago, I noticed a robin building a nest on my neighbor's porch. Not just any neighbor's porch, but the neighbor with the four active young boys that my kids love to play with in their yard. What was that robin thinking, I wondered? How would it ever pull off raising a brood with all those kids running around in the yard?

Well, I'm not sure how it happened, but those robins did so marvelously! The nest is now empty, and after watching the robins go from being eggs to noisy squawkers, all the neighborhood kids want is for the birds to return and raise another batch of young. Who am I to say what is a good place for a bird to build its nest? In this case, the seemingly poor choice turned out great. Amazing.

Well, I'm not sure how it happened, but those robins did so marvelously! The nest is now empty, and after watching the robins go from being eggs to noisy squawkers, all the neighborhood kids want is for the birds to return and raise another batch of young. Who am I to say what is a good place for a bird to build its nest? In this case, the seemingly poor choice turned out great. Amazing.

Friday, June 13, 2008

I need a mockingbird

After driving my kids to school this morning, I've got 19 species for the day. The temps are in the 90s. I've no desire to go out for a walk. I need one more species to get my Bird RDA. I need a mockingbird!

UPDATE: Got the mockingbird, and several other birds including Eastern Kingbird, in the afternoon.

UPDATE: Got the mockingbird, and several other birds including Eastern Kingbird, in the afternoon.

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

Birding Withdrawls

After several days of great birding this past week, today I've got the shakes from birding withdrawls! I did easily manage 23 species on my drive into the office. And another two species on the way home. While that may be enough to prove that I'm still alive, it doesn't quench the birding thirst!

Must...get...more...birds!

Must...get...more...birds!

Monday, June 09, 2008

Little Egret

(photo: Howard Eskin)

Last night when we got back to PA from NC, we were a bit chagrined to find that a Little Egret had been seen on Saturday and Sunday just a few miles from where we had passed by on our return trip. So early this morning, we headed back down to Bombay Hook NWR in Delaware to search for the rare Eurasian wader.

We arrived shortly before 7am to find another birder already watching the bird in his scope. After a few minutes, the egret flew off, and we quickly relocated it in another pool, where we watched it shuffling its straw-colored feet in the water to scare up small fish.

A truly neat looking bird with its two long white feathers sticking out behind its head. A fitting end to a long weekend full of fantastic birds!

Manteo Pelagics

On Friday and Saturday, I enjoyed, for the first time, pelagic trips without pain. After many touch and go trips, I finally got "the patch" and had two great pelagic trips without any queasiness. A miracle!

Friday the winds were up and the seas a bit choppy as we headed out to the deep water. We had Wilson's and Band-rumped Storm-Petrels following our boat for most of the day, and I managed to see one Leach's Storm-Petrel come in.

Shearwaters were few and far between, and we only had Cory's and Audubon's.

Gadfly petrels were seen off and on, but almost always at a great distance. We only positively identified Black-capped Petrels. None of the more uncommon or rare ones.

Saturday was a completely different day. Skies were more sunny, less wind, and the seas were smooth. Too smooth, and probably too calm, as we had a tough time finding Gadfly petrels and other birds that use the wind to get around out there. Most birds we found were on the water.

When we hit the Sargasso weed patches, we had tons of birds. Mostly Audubon's Shearwaters and Wilson's Storm-Petrels. Far fewer Band-rumps. And only a small handfull of Black-capped Petrels. But we did get Bridled Tern, Parasitic Jaeger, and Greater Shearwater.

But the stars of Saturday were the whales and dolphins. We had a total of 14 sperm whales! Several very close to the boat. We also had a pod of pilot wales. We had several groups of offshore bottlenosed dolphins. And at one point we had a large group of Atlantic spotted dolphins jumping completely out of the water. On the way back in we were surrounded by maybe 500 common dolphins leaping together and streaming past the boat. Amazing. Its another world out there!

Other highlights included Portuguese Man-of-War, Loggerhead sea turtles, blue marlins, yellow-finned tuna, and mahi-mahi. And of course thousands of flying fish!

Low points were quick or distant looks at birds which may have been good rarities--but not confirmed by other members of the trip (British Storm-Petrel, Bahama Petrel, and Fea's Petrel). Note to potential pelagic birders: you will see more birds if you continuously scan the ocean with your binoculars. If you wait for someone to point birds out to you, you will miss a whole lot. For a good part of both trips most participants were just standing there, I suppose waiting for birds to come in close. I think I probably saw hundreds of birds more than many of the other participants, mostly by scanning continuously.

Again, thanks to the patch! This would have been unthinkable on my previous trips.

So, if you're going offshore, get some drugs if you need to. The patch is a performance enhancing drug, for sure!

Can't wait to get back out on the ocean and take another crack at finding some rare seabirds!

Friday the winds were up and the seas a bit choppy as we headed out to the deep water. We had Wilson's and Band-rumped Storm-Petrels following our boat for most of the day, and I managed to see one Leach's Storm-Petrel come in.

Shearwaters were few and far between, and we only had Cory's and Audubon's.

Gadfly petrels were seen off and on, but almost always at a great distance. We only positively identified Black-capped Petrels. None of the more uncommon or rare ones.

Saturday was a completely different day. Skies were more sunny, less wind, and the seas were smooth. Too smooth, and probably too calm, as we had a tough time finding Gadfly petrels and other birds that use the wind to get around out there. Most birds we found were on the water.

When we hit the Sargasso weed patches, we had tons of birds. Mostly Audubon's Shearwaters and Wilson's Storm-Petrels. Far fewer Band-rumps. And only a small handfull of Black-capped Petrels. But we did get Bridled Tern, Parasitic Jaeger, and Greater Shearwater.

But the stars of Saturday were the whales and dolphins. We had a total of 14 sperm whales! Several very close to the boat. We also had a pod of pilot wales. We had several groups of offshore bottlenosed dolphins. And at one point we had a large group of Atlantic spotted dolphins jumping completely out of the water. On the way back in we were surrounded by maybe 500 common dolphins leaping together and streaming past the boat. Amazing. Its another world out there!

Other highlights included Portuguese Man-of-War, Loggerhead sea turtles, blue marlins, yellow-finned tuna, and mahi-mahi. And of course thousands of flying fish!

Low points were quick or distant looks at birds which may have been good rarities--but not confirmed by other members of the trip (British Storm-Petrel, Bahama Petrel, and Fea's Petrel). Note to potential pelagic birders: you will see more birds if you continuously scan the ocean with your binoculars. If you wait for someone to point birds out to you, you will miss a whole lot. For a good part of both trips most participants were just standing there, I suppose waiting for birds to come in close. I think I probably saw hundreds of birds more than many of the other participants, mostly by scanning continuously.

Again, thanks to the patch! This would have been unthinkable on my previous trips.

So, if you're going offshore, get some drugs if you need to. The patch is a performance enhancing drug, for sure!

Can't wait to get back out on the ocean and take another crack at finding some rare seabirds!

Saltmarsh Sharp-tailed Sparrow

On our way down to North Carolina for some pelagic birding, we made a few stops in Delaware to look for Saltmarsh Sharp-tailed Sparrow--a small sparrow with an orange breast with brown streaks that would be a new species for my friends from Montana.

Our first stop was the boardwalk at Bombay Hook NWR. Despite dozens of Seaside Sparrows flying around and perching close by, we couldn't come up with any Saltmarsh Sparrows (Isn't that a better name, BTW?).

Then we headed down to the Dupont Nature Center, and after two hours of searching the marsh there we finally got a fifteen second look at one Saltmarsh Sparrow looking at us in some short grass. Unfortunately, only two of us saw it, so one of my friends had to leave without the desired lifer. No fun, that!

Our first stop was the boardwalk at Bombay Hook NWR. Despite dozens of Seaside Sparrows flying around and perching close by, we couldn't come up with any Saltmarsh Sparrows (Isn't that a better name, BTW?).

Then we headed down to the Dupont Nature Center, and after two hours of searching the marsh there we finally got a fifteen second look at one Saltmarsh Sparrow looking at us in some short grass. Unfortunately, only two of us saw it, so one of my friends had to leave without the desired lifer. No fun, that!

Wednesday, June 04, 2008

Off to Manteo

I'm off tomorrow for a couple pelagic trips off Manteo, NC. Lots of good birds have been seen offshore there this season, so wish me luck!

Monday, June 02, 2008

Few and far between

I'm still alive. I saw an Eastern Kingbird, and 22 other species today. Mostly on my drive into work. I've got a big birding trip coming up this weekend, but other than that, I'm just barely getting my minimum Bird RDA these days!