Photo guides have come a long way since those days, but there are still lots of questions about the limitations of a photo field guide to birds. To examine those, lets take a look back through time.

1977 Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region (John L. Bull, John Farrand, National Audubon Society).

This was pretty much the first photo guide, and the companion to the red-covered Western version I first saw. The vinyl cover made it waterproof and seem pretty rugged. That was nice. The photos were supposed to be arranged by similarity--both by shape (here we have some shorebirds) and by color--so if you thumbed back a bit farther you would get goldfinch and warbler photos close to each other, since they are both yellow. There was usually just one photo per species. All the photos were together at the front of the book, with all of the text in the latter part of the book. The text was actually pretty good, with lots of stuff about habits and habitat. It was mass produced, and the latest edition is still in print.

In the pre-National Geographic field guide era (up to 1983), this guide was one of the big three (along with Peterson's and the Golden Guide) popular bird guides. Lots of folks were attracted by the photos, and then were probably stuck with an attractive book that probably wasn't as easy to use to actually identify birds as were the other two books--which showed more species closer together and in more plumages.

Truth be told, I never bought a copy of these guides, even though you can find them at garage sales for almost nothing. I should probably pick one up for historical reasons next time I see one at the thrift store, but I've never bothered. In the early 1980s I thought this was the least useful of the major three guides, and now there are many more comprehensive and useful photo guides.

1983 The Audubon Society Master Guide to Birding, edited by John Farrand, Jr.

These three volumes were the first must-have photo guides. In order to compete in the serious bird guide market with the National Geographic Guide, these three volumes really were must-have books when they first came out. As the original tag line sold it, these guides covered

"all 835 species of birds recorded on the continent, including 116 accidentals, this is the first field guide to North American birds specifically designed to satisfy the interests of the serious birder. Its three volumes contain, in all, 1245 full-color photographs, 193 paintings, 422 drawings, and 650 range maps, while 61 of the nation’s top field ornithologists and experts contribute their special knowledge to the 370,000 words of text. Entries are arranged taxonomically to the new American Ornithologist’s Union Classification"

The guide featured text and photos (some paintings) on opposite pages, with tons of info geared towards field identification--most especially the detailed description and similar species sections. While in three volumes, it wasn't designed to be carried into the field, it did serve as a valuable identification aid and reference for checking up on bird identifications back home, or to bone up for birding trips. In my view, the best photo guides have been along these lines--specialized books not to be taken into the field, but to serve as identification resources back home--eg. The Shorebird Guide, Hawks from Every Angle, etc.

1988 An Audubon Handbook Eastern Birds, by John Farrand, Jr.

One more attempt to make a decent photo guide by John Farrand and Audubon, this vinyl covered book had a similar size and feel to the earlier Audubon guides, but now featured photos and text on the same page. The number of photos was still limited--though most species featured more than one photo, for a total of 1,354 photos of just over 460 species.

There was actually a lot of good to be said for this book, with each species getting its own page--even such rarities as Brown Jay. The photos were mostly pretty good, and there was much more text for each species than found in many recent guides--including a similar species section, which is most helpful for birders trying to make sure they aren't examining all their options when identifying a bird.

I never bought this book when it came out (I was in South America for a couple years), but the more I look at it now, the more I like it. But it does suffer from the biggest complaint about photo ID books--they only show individual birds, while an artist's illustration may be able to show a more standardized or representative view of a bird's plumage, posture, etc. Photo guides also suffer because the individual photos may be taken under very different lighting conditions, making it tough to really compare one photo with another--which can occasionally lead to errors in identification when color artifacts in the photos are used as field marks.

1996 Stokes Field Guide to Birds, Eastern Region, by Donald & Lillian Stokes

This is another book I passed on when it first came out, mostly due to the limitations in format. Similar to the Farrand handbook, this one has one species per page--which is generous when it comes to text, but with most species only getting one photo. The photos are pretty good, some are even stunning. There is no similar species section, but many notes on how to distinguish from most similar species are emphasized (in bold--a bit distracting at least for me) in the identification section of the text.

This is another book I passed on when it first came out, mostly due to the limitations in format. Similar to the Farrand handbook, this one has one species per page--which is generous when it comes to text, but with most species only getting one photo. The photos are pretty good, some are even stunning. There is no similar species section, but many notes on how to distinguish from most similar species are emphasized (in bold--a bit distracting at least for me) in the identification section of the text.

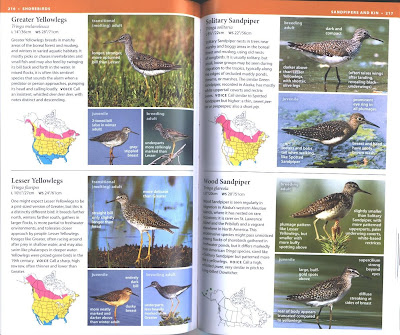

Again, with photos you don't have enough room to show all the plumages, so that's the biggest limitation. But even then, sometimes a reader is left to wonder why only one photo for a species like Wild Turkey (showing a pretty rangy looking hen), when many other sexually dimorphic birds get photos of both male and female birds? Of course, for beginners, you have to wonder how many plumages they really need to see. So it becomes a question of audience. For beginners, a field guide really needs to walk them through how to identify every bird--so you need good similar species discussions and other helpful tools, like comparison images. The Learning Pages for each bird family, easily found with colored tabs tied to a quick index inside the front and back cover, really helped here. But in a photo field guide organized with one species per page, you often don't even get the most similar species on facing pages, as in this case with Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs on separate page layouts.

So, photos are just mostly OK here, but the text is pretty good and lots of good info, helpfully broken into sections. As an aside, when it came out it was good to see conservation emphasized, if somewhat cryptically, in its own section per species.

2000 Kaufman Focus Guide, Birds of North America, Kenn Kaufman

While technically a photo guide, since it uses digitally enhanced photographic images of each species, this really is more of a traditional guide, in many ways similar in format to the old Golden Guide, which was a favorite of many for packing a ton of info into its tight format. In this case, Kenn Kaufman was able to avoid perhaps one of the biggest problems with photo guides--the "bulkiness" of the photos. While booksellers may laud the virtues of a bird being shown in its natural habitat, in reality, most bird photos only end up showing empty sky, water, leaves, or other unhelpful background, rather than useful habitat info. In addition, all that water or leaves take up so much room that its hard to get more images in of birds in additional plumages, poses, etc. While an artist can pack many images of a species into a tight space, photo guides are usually limited by the blocky rectangles of photos.

While technically a photo guide, since it uses digitally enhanced photographic images of each species, this really is more of a traditional guide, in many ways similar in format to the old Golden Guide, which was a favorite of many for packing a ton of info into its tight format. In this case, Kenn Kaufman was able to avoid perhaps one of the biggest problems with photo guides--the "bulkiness" of the photos. While booksellers may laud the virtues of a bird being shown in its natural habitat, in reality, most bird photos only end up showing empty sky, water, leaves, or other unhelpful background, rather than useful habitat info. In addition, all that water or leaves take up so much room that its hard to get more images in of birds in additional plumages, poses, etc. While an artist can pack many images of a species into a tight space, photo guides are usually limited by the blocky rectangles of photos.Kenn Kaufman fixed that by just digitally taking the backgrounds out and photoshoping all the images into nice groups.

This isn't the place for a full review of this book, which I still consider probably the best field guide for beginners, but it is good to note that even though the text is spare, similar species are usually shown closely together, arrows point out field marks (though you usually have to supply your own discussion of those marks by comparing arrows on the photos), and there are usually more images per species than in previous photo guides (eg. two Philadelphia Vireo shots, as compared to just one in the Farrand and Stokes guides, and four vs. three shots of Least Tern).

Enter the latest 21st century photo bird guides, out within the last year...

2007 National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Birds of North America, by Edward S. Brinkley

This isn't the place for a full review (look for that here soon!), but here's a quick first look. This book claims 2,100 photos of over 750 species. That's a lot of birds, and a lot of photos. Most birds get half a page, and all the text, maps, and photos have to be crammed into there. In order to do this, all the text on identification is superimposed on the photos, making it pretty spare. Whereas some of the older photo guides emphasized text more than photos, this guide is really stripped down. No similar species section here!

This isn't the place for a full review (look for that here soon!), but here's a quick first look. This book claims 2,100 photos of over 750 species. That's a lot of birds, and a lot of photos. Most birds get half a page, and all the text, maps, and photos have to be crammed into there. In order to do this, all the text on identification is superimposed on the photos, making it pretty spare. Whereas some of the older photo guides emphasized text more than photos, this guide is really stripped down. No similar species section here!

What you do get are some decent (some are even stunning) photos of each bird, including some that aren't covered in some of the more popular guides. Can't find Wood Sandpiper in your Sibley? Well here's a couple photos. Many other rarities are also featured. Editorially, again sometimes the reader is left scratching his or her head--while I'm tickled to see a photo of a baby American Oystercatcher, how useful is that shot in a field guide? Especially when other chicks aren't featured? Show me a whole plate of baby shorebirds, then I'd be happy (and really impressed, ever try to find photos of a baby Long-billed Curlew online?)!

2008 Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America, by Ted Floyd

Again, not the place for a full review (see that here later!), but here's a first look at this guide, which takes both a similar and yet different approach than the NWF guide. The layout of this guide is very attractive, with a half page (either vertical, or sometimes horizontal) dedicated to most species. As with the NWF guide, identification text is attached to each photo, but here as a caption rather than superimposed on the image.

Again, not the place for a full review (see that here later!), but here's a first look at this guide, which takes both a similar and yet different approach than the NWF guide. The layout of this guide is very attractive, with a half page (either vertical, or sometimes horizontal) dedicated to most species. As with the NWF guide, identification text is attached to each photo, but here as a caption rather than superimposed on the image.

In a guide dedicated to showing "the natural variation within and among species", the space-limiting nature of photo guides seems to be a big problem. Whereas other field guides show lots of images of Glaucous-winged Gull, how useful is this treatment where we only get one image of an adult (in flight) and the other two images in the species account are of standing adult and immature hybrid Western X Glaucous-winged Gulls? No doubt its fun to look at photos of hybird gulls (if you are into that kind of thing), but again, who is this guide for? Maybe this isn't the best example, because average birders may not even attempt to identify Glaucous-winged Gulls. But having grown up birding in Oregon, even as a newer birder, not having more images of this species would have been a big bummer for me.

There'll be time for more in depth coverage of this guide in the full review. For now, these last two books seem to highlight a couple of funny places we seem to be in as consumers of bird identification materials.

Ubiquitous bird photos: While its tough (and darn expensive) to come up with great color illustrations of birds, amazing digital bird photos are everywhere now. That makes coming up with a photo guide easier than ever before. And the later books have many more and better images than ever before. However, in the day when a Google image search can bring up dozens of shots of most bird species, what is the place for a photo guide? With the space limitations imposed by the photos, and for the other limitations noted above, it makes it tough for these books to function as well as a field guides. As a reference back home, its getting tougher to beat the Internet.

Audience: What is the audience for field guides? Advanced birders, who usually don't need them in the field, but may use them as reference materials at home? Again, why do they need a book, rather than the Internet? What about beginners? What type of info do they really need, and how can it be best presented in a field guide? I have a lot of admiration for all of the books I've featured here (even the old green and red vinyl Audubon guides had their moments), but for beginners, I'm not sure we've hit on the best recipe for a field guide, and I'm not convinced that traditional photo guides are going to be their biggest aid.

Its an exciting time, with more resources available than ever before. Photo guides will always have their place, but it remains to be seen (through sales, and use) exactly what that place will be as we move further into the 21st Century. I hesitate to even guess what that place might look like five, ten, or more years down the road!

9 comments:

I began birding late in life, and my first field guide was a little pocket book by Sgtan Tekiela called Birds of the Carolinas. Photos, arranged by color and size of the bird, made it ideal for me as a beginner. Of course, I outgrew it quickly, but it sure got me off to a good start!

It's interesting to see all of them together. I had forgotten about the "master guide" when I did my review, and I never knew about the later Farrand guide. I think it is very hard to put together an effective photographic field guide, without following the Kaufman model.

Wow, fantastic job. I think your analysis is right on. You put my similar effort to shame!

Internet-published photos may indeed make such books obsolete. But not until there is an extensive and expert-vetted archive. Anyone can post bird pictures, but it doesn't mean they are correctly identified and labeled. So published guides may have a little life left in them. (and not that the books don't mislabel photos!)

I've picked up the Farrand and Master guides, but haven't looked through them very much. I need to do that eventually...

Thanks for this lucid analysis. My personal preference lies with the illustrated Field guide versus the photographic ones, and you've aptly pointed out why that is.

There probably is a market for a subscription based, expert vetted on-line guide. Now we need someone to take up that torch.

Good stuff, Rob! In its current print-bound stage, the photographic field guide is a fine model for "specialty" guides (Steve Howell's Hummingbirds, his and Jon Dunn's Gulls, Richard Crossley's Shorebirds), but not yet practical for a truly advanced field guide to a continental avifauna--I think the first really definitive photo guide to a continent or region will be an e-guide (and Ted Floyd's excellent Smithsonian volume points the way to the future with its dvd component).

Thanks again for this essay,

Rick

Grant, you're too humble. Your list comparing photo field guides is cool, and your review of the Smithsonian guide is the best I've seen so far (just wait for mine!).

Rick, I think you are right. Wanna start that online guide with me?!?

Thanks, Rob! And I do look forward to reading your full review.

This post is great! I can remember flipping through all of those older guides in my younger days (except for Stokes, I don't think I've ever thumbed through that one).

Thanks for your overview of the photo guides, which I really enjoyed.

Bird guide users - and bird lovers, of course - will also like my new book, Birdwatcher: The Life of Roger Tory Peterson, out now from The Lyons Press.

Peterson played a central role in the expansion of birding not only in the US, but also Europe and East Africa. My book details these things, as well as demonstrating the breadth of his involvement and leadership in nature education and many of the most celebrated conservation causes of the 20th century. From his early 20s onward, Peterson was teaching about all aspects of nature, sometimes informally, sometimes formally, through his writings, lectures, books and work with various conservation organizations.

Also, the reader learns about Peterson the Man: what motivated him, personal and professional challenges he faced, and his personal impact on many of today's top birders and conservationists.

I ended up talking to well over 100 people from around the world to put together this portrait of a complex and driven man. Birders, natural history buffs, and conservationists alike will enjoy the book.

If anyone has any questions, please feel free to e-mail me at ejrose@aol.com.

Thanks.

Post a Comment