John Puschock is a Seattle-based bird tour leader and owner of

Zugunruhe Birding Tours, which offers tours to far-flung birding hot spots including the fabled Attu Island in the Aleutians. I've been dreaming about going to Attu since the early 1980s, when I first read about it in James Vardaman's classic recounting of his 1979 North American Big Year

Call Collect, Ask for Birdman. In 1995, when I was planning my own North American Big Year as a fundraiser for Audubon (but that's another story), I actually paid the $300 down payment for a spring trip to Attu, but when Audubon pulled its support for the venture and I lost that deposit and a few years later

Attour closed down its trips. It looked like my chances of getting to Attu, and seeing dozens of cool Siberian vagrant birds in North America, were gone for good. A few years ago Victor Emanuel Nature Tours stopped by Attu, and last year Zugenruhe started offering boat-based trips there again. So perhaps I can still get out there yet!

I first met John Puschock back in 2006 when I was out in San Diego. I found a locally rare

Marbled Murrelet off La Joya Cove, and John was one of the incredulous birders who showed up to look for it for several days before it was rediscovered and

my sighting was vindicated. The funniest thing I remember about hanging out with John at La Jolla Cove was when I asked if I could borrow his scope, and he said I could as long as I didn't have pink eye. Funny guy!

Anyway, I've kept up with John off and on over the past few years, and am happy to have him join me on here for a Birdchaser Interview:

BIRDCHASER: So, when we met back in 2006, were you already leading tours then?JP: First off, if the line about the pink eye was the funniest thing you

remember, I must have been having an off day. Sorry about that ;-)

And yes, I started leading tours in 2004 for

Bird Treks, and when I moved to San Diego in 2005, I also began a business doing day trips around southern CA. I’ve since moved to Seattle and started Zugunruhe Birding Tours, but I still work for Bird Treks, too. But I’ve dropped the San Diego day trip portion of the business since the commute was a killer.

B: How did you start going to the Aleutians?JP: The long version of the story begins with me not seeing a Gray-headed Chickadee, at least not definitively, while working in northwest Alaska in 1998. But no one wants to read a long story on a blog...The short version is I read Ted Floyd’s account of his trip to Adak in Aug 2003 and that the island was becoming accessible to the general public, so I asked Bob Schutsky, owner of Bird Treks, if he’d be interested in working with me to develop a tour there. He said yes.

B: What have been some of your best birding experiences on Adak?Literally at least ten things come to mind, but I’ll try to pare it down...Every time we go out on a boat to look for Whiskered Auklets is special. I’ve seen quite a few now, but it’s still a mythical bird to me. Seeing one just twenty feet away never gets old.

I’ve seen four Marsh Sandpipers on Adak, and those were all great. The last two were together, and I had seen one a week earlier when I didn’t have a group with me. I told the tour participants about that bird (the one I saw by myself) before they got there, and that I didn’t expect it to stick around long enough for them to see it. I was right about that, so finding another two while my group was there more than made up for that – snatching victory from the jaws of defeat added to the excitement.

But my favorite experience was finding an Eastern Spot-billed Duck. It was late in the day, probably 9 PM, and unfortunately I didn’t have a group with me at the time – I had stayed a few extra days after my group had left – so I was driving around Clam Lagoon by myself. I surprised a group of Mallards near the road, and they all jumped. I put my binoculars on part of the group flying away and thought to myself, “That one looks different.” It landed, I got a quick scope view, and I was soon flying down the road back to town to get the other birders on the island. Some of them were already in bed, but everyone came out for it.

B: How did you end up deciding to do trips to Attu?JP: I’ll go with the short version again: I found a boat that was close enough to Adak to make the trip financially feasible. I know a few others had tried to get there since Attour closed up shop, but the stumbling block always was finding reasonable transportation. The closest appropriate boats had been in southeast Alaska, and the cost of getting them to the Aleutians was prohibitive. Luckily, I found out about a boat, the

Puk-Uk, in Homer.

B: There was a serious Attu birding culture and community that developed around Attour. Are you getting some of those old Attuvians coming back now on your tours?JP: I had one Attour Attuvian on last year’s trip (our first), two who were on the VENT trip in the fall of 2006, plus one of my guides, Mike Toochin, was an Attour guide throughout the 90s. Now that we’ve proved we can do the trip and I’ve been able to drop the price too, I’m hoping some more will join us. I’ve always been interested in the history and tradition of birding, so it would be great to hear stories about the old days.

B: How are trips to Attu different now than they were back in the glory days of Attour?JP: We sleep and eat on the boat now, not the old buildings that Attour used. Those building are still there, by the way, along with everyone’s list totals written on the walls. There are fewer people on our trip, but otherwise I think it’s pretty similar. We have bikes to get around, and it’s still windy.

B: Given that some years are better than others, what should a birder expect to be able to see on your Attu trips?That’s a tough question if you’re asking about Asian vagrants. Last spring, the Aleutians were plagued with north winds for weeks. That’s not the direction you want the winds to be blowing for vagrants, and we did miss some that I thought were a sure thing: Lesser Sand-Plover and Common Sandpiper come to mind. We also had low numbers of Wood Sandpipers (3) and Long-toed Stint (1). But we did get other “expected” species such as Rustic Bunting and Brambling, plus other less-expected species like Hawfinch, Red-flanked Bluetail, and

the bird of the trip, the first accepted North American record of Solitary Snipe. Of course, the species normally resident in the Aleutians and Bering Sea would be expected. We saw tons (probably literally) of alcids, included Whiskered Auklet. We saw every seabird expected and not-so-expected in the area, including Short-tailed Albatross, Mottled Petrel, and Red-legged Kittiwake. The bottom line is that a birder can expect to see vagrants and other cool birds that can't be entirely predicted, though the Whiskered Auklets are very likely.

B: Can birders see as many birds on Attu with these smaller groups as they did back in the day when there were larger groups potentially covering more parts of the island?JP: I’m sure we’ll miss a bird here and there with our smaller group, but I think we’ll get most of them. For a long time, I thought you could only bird the island with a large group, but then the thought occurred to me that Univ. of Alaska-Fairbanks has been sending a team of two to the island for years to collect specimens, and they’ve been turning up good birds all the time. If two could do that, certainly ten could do even better.

BP: For the cost of an African safari, why should someone bird Attu or the Aleutians? What makes the Aleutians, and Attu in particular, so special?I’m not going to tell anyone they

should bird the Aleutians. Everyone has different interests. Even among the Attour crowd, people came for different reasons. From what I’ve heard, there were even a few who weren’t birders. But I will say why someone might enjoy it:

The Aleutians are a corner of the world that’s unlike anywhere else and almost certainly completely different than where you live. In that respect, it’s the same as an African safari or any other exotic location. It’s wild and remote. It’s an expedition. I like the excitement of not knowing what I might find...and then the excitement of finding it. And while Attour was finding all those first North American records, Attu was elevated to legendary status among birders, so there’s that aspect to it, too -- walking around Lower and Upper Base (where Attour used to stay) was like being in a shrine. Of course, if you want to pump up your ABA list, there’s no better place to go, particularly if it’s your first visit to the Bering Sea region.

There’s always that cost-per-bird issue with trips like this (and implicit in your question). If you’re a world birder, particularly if you’ve already seen the Beringian endemics like Whiskered Auklet and Red-legged Kittiwake, and your interest is getting more life birds, frankly there’s no reason to go to Attu. But if you’re into your ABA list, then this trip makes more sense, especially if you haven’t been to Alaska before. It would save having to make a separate trip for the Auklet, plus you may see all the resident species you would see at St. Paul, possibly saving a trip there (though admittedly the experiences would be different – at St. Paul you get to see the seabirds from close range while both you and the birds are on land).

I like to do trips that go beyond just ticking off lifers and are about the quality and/or uniqueness of the experience, and this is one of them. As an aside, I just got back from a tour that was my favorite ever – great birds, great people – and the trip list was only 19 species. No lifers for me, but among the 19 were Ross’s and Ivory Gulls, Spectacled Eider, and Snowy Owls. Gotta love that...But I don’t have anything against racking up a big trip list, either.

My answers are getting too long. How about some simple questions that don’t require me to think too much?

B: OK, before we finish up, maybe you could tell us your favorite thing about being a birding guide?JP: The vicarious excitement of tour participants getting lifers and experiencing new things, but that isn’t unique to being a guide -- from my experience, just about every birder enjoys helping someone else find a bird. Getting to travel more than I would otherwise is another job benefit. I know you asked for just one thing but I’m giving you two.

That was my real world answer. My fantasy world answer would be something like this: Children running up and wanting me to autograph their binocular straps, the defeated and embarrassed look on old classmates’ faces at a high school reunion when they find out I’m a birding guide and they’re just brain surgeons and astronauts, all the attention from the ladies, and of course the money. That’s my fantasy world answer!

B: What advice might you give to potential tour participants about choosing the best tour for them?JP: Wings (the tour company, not the band) has an

essay on their website that has just about all the advice anyone would need, so even though I’m directing your readers to a competitor’s website, my advice would be to read that essay. The only additional advice would be to check with the tour operator to see when you’re expected to wake up in the morning. Not everyone enjoys getting up at o-dark-thirty.

B: And to get us out of here, gazing into your crystal ball, what new or upcoming trends do you see in birding and bird touring?JP: Before I answer that, I want to say that if you’re not part of any trends, it doesn’t mean you’re a substandard birder. I don’t want to give the impression that you have to be part of a trend to be “with it”, and what we think of as birding will remain 98% unchanged, just as it has been since shotguns were traded in for field glasses. Also, these trends will be felt most by those of us for whom birding is a lifestyle (e.g., anyone reading your blog). With that said...

There will be an acceleration of the instant access to information that began in the early- to mid-90s due to wider use of and improvements in smartphone-type mobile devices, but it doesn’t take a crystal ball to see that coming since listservs already have real-time updates coming in from iPhones and Blackberries.

Soon no one will be complaining about a field guide being too big to carry in the field because with color e-book readers and iPads we’ll be able to carry a birding library on one small device.

Birders will take advantage of their mobile devices and cameras with audio recording capability to make more sound recordings. This will eventually lead to less fear of any Red Crossbill splits.

One trend I hope to see in the next two years is a resurgent ABA. For that to happen, I think they need to start broadening their focus and also make the internet work for them instead of against them as it has been. For example, they could create members-only wiki site guides and convert their membership directory into a Facebook-like website. I wrote

a lot more on that subject on my blog. You may want to check it out if you’re having trouble sleeping. Another thing I hope to see is a book about Guy McCaskie and/or the 1970s California birding scene.

In the realm of bird tours, I think multi-day pelagic trips will grow somewhat, and some “new” destinations, both within the ABA Area and worldwide, will become more popular. I could go into some of that in more detail, but I don’t want to beat you over the head with the self-promotion. ;)

Looking further into the future, mobile devices will be able to take a picture of a bird and identify it, leading us to debate if that’s really “birding” or not. While we’re arguing about that, our machines will become self-aware, realize human birders are unnecessary, and

attempt to exterminate us all. After that, a certain someone in Arizona will finally complete his guide to flycatchers, something I’ve been waiting for since 1997.

B: Thanks John, hope to be out birding with you again soon, and not just visiting here on the interwebs. Best of luck on Attu--may all your trips be filled and first North American records abound!JP: Thank you, Birdchaser!

What hazards are killing birds? How does our society deal with these hazards?

What hazards are killing birds? How does our society deal with these hazards?  Here's a recent list from the BBC's Stephen Moss. Heavy emphasis on the BRIT in celeBRITy here, no mention of American birdwatchers including Jimmy Carter, Laura Bush, Jane Alexander, Wes Craven, or Daryl Hannah.

Here's a recent list from the BBC's Stephen Moss. Heavy emphasis on the BRIT in celeBRITy here, no mention of American birdwatchers including Jimmy Carter, Laura Bush, Jane Alexander, Wes Craven, or Daryl Hannah.

The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America is a colossal wonder. As advertised, it has:

The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America is a colossal wonder. As advertised, it has:

John Puschock is a Seattle-based bird tour leader and owner of Zugunruhe Birding Tours, which offers tours to far-flung birding hot spots including the fabled Attu Island in the Aleutians. I've been dreaming about going to Attu since the early 1980s, when I first read about it in James Vardaman's classic recounting of his 1979 North American Big Year Call Collect, Ask for Birdman. In 1995, when I was planning my own North American Big Year as a fundraiser for Audubon (but that's another story), I actually paid the $300 down payment for a spring trip to Attu, but when Audubon pulled its support for the venture and I lost that deposit and a few years later Attour closed down its trips. It looked like my chances of getting to Attu, and seeing dozens of cool Siberian vagrant birds in North America, were gone for good. A few years ago Victor Emanuel Nature Tours stopped by Attu, and last year Zugenruhe started offering boat-based trips there again. So perhaps I can still get out there yet!

John Puschock is a Seattle-based bird tour leader and owner of Zugunruhe Birding Tours, which offers tours to far-flung birding hot spots including the fabled Attu Island in the Aleutians. I've been dreaming about going to Attu since the early 1980s, when I first read about it in James Vardaman's classic recounting of his 1979 North American Big Year Call Collect, Ask for Birdman. In 1995, when I was planning my own North American Big Year as a fundraiser for Audubon (but that's another story), I actually paid the $300 down payment for a spring trip to Attu, but when Audubon pulled its support for the venture and I lost that deposit and a few years later Attour closed down its trips. It looked like my chances of getting to Attu, and seeing dozens of cool Siberian vagrant birds in North America, were gone for good. A few years ago Victor Emanuel Nature Tours stopped by Attu, and last year Zugenruhe started offering boat-based trips there again. So perhaps I can still get out there yet! A couple years ago I charted the rise of the bird photo field guide. Since then, several new photo field guides have come out, including the Stokes guide that is out this month, and the photographic field guides of Paul Sterry and Brian Small that came out last year. And everyone is waiting to see Richard Crossley's field guide scheduled to come out next year.

A couple years ago I charted the rise of the bird photo field guide. Since then, several new photo field guides have come out, including the Stokes guide that is out this month, and the photographic field guides of Paul Sterry and Brian Small that came out last year. And everyone is waiting to see Richard Crossley's field guide scheduled to come out next year. A) Large photos: Photos in these guides are generally generously sized--which is good in that they provide a nice look at the birds, but may be bad in that they take up so much room that we don't get as many photos of each species. The beautiful photos, most by Brian Small, are easily the best feature of these guides.

A) Large photos: Photos in these guides are generally generously sized--which is good in that they provide a nice look at the birds, but may be bad in that they take up so much room that we don't get as many photos of each species. The beautiful photos, most by Brian Small, are easily the best feature of these guides.

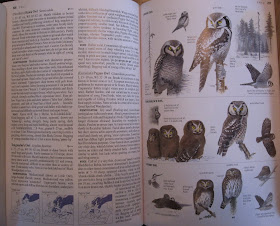

Earlier this year Princeton University Press (in the US) published Lars Svensson, Killian Mullarney, and Dan Zetterström's Birds of Europe: 2nd Edition (published in Europe by HarperCollins as the Collins Bird Guide). There are some glowing reviews out there (see links here), to which I need to add my own.

Earlier this year Princeton University Press (in the US) published Lars Svensson, Killian Mullarney, and Dan Zetterström's Birds of Europe: 2nd Edition (published in Europe by HarperCollins as the Collins Bird Guide). There are some glowing reviews out there (see links here), to which I need to add my own. Captions of text with lines pointing to relevant plumage features as well as notes on important behaviors are included on the illustrations themselves, putting the information right where you need it most. If you are a fan of photo guides, you really need to get this guide so you can see how much better good illustrations are at conveying the information needed for comparing and identifying bird species. The text in the main section and the caption points out what are most important--be they details of feathers, or more general impressions of shape and size (GISS or jizz). I love how Hawk Owls are noted to have a "grim look" while Tengmalm's Owl--our Boreal Owl--is noted to have an "astonished look" and the European Pygmy Owl is depicted as having an "austere look"--important and unique facets of a bird's overall appearance that you won't find in most other guides.

Captions of text with lines pointing to relevant plumage features as well as notes on important behaviors are included on the illustrations themselves, putting the information right where you need it most. If you are a fan of photo guides, you really need to get this guide so you can see how much better good illustrations are at conveying the information needed for comparing and identifying bird species. The text in the main section and the caption points out what are most important--be they details of feathers, or more general impressions of shape and size (GISS or jizz). I love how Hawk Owls are noted to have a "grim look" while Tengmalm's Owl--our Boreal Owl--is noted to have an "astonished look" and the European Pygmy Owl is depicted as having an "austere look"--important and unique facets of a bird's overall appearance that you won't find in most other guides. I recently got in trouble for suggesting that birders are too geeky. Turns out there are plenty of famous and cool people who are not only birders, but bird blog readers. As I set out to do this latest I and the Bird, I checked some celebirdy Twitter feeds and found I could do a whole I and the Bird just by retweeting their tweets!

I recently got in trouble for suggesting that birders are too geeky. Turns out there are plenty of famous and cool people who are not only birders, but bird blog readers. As I set out to do this latest I and the Bird, I checked some celebirdy Twitter feeds and found I could do a whole I and the Bird just by retweeting their tweets! RT @Brangelina We love birding with the kids, thanks N8 for showing us how http://tinyurl.com/3afoyd7

RT @Brangelina We love birding with the kids, thanks N8 for showing us how http://tinyurl.com/3afoyd7 RT @LadyG ooh la la egret pics http://tinyurl.com/2fvx2xn

RT @LadyG ooh la la egret pics http://tinyurl.com/2fvx2xn RT @IceT Me and Coco gotta get more of that global birding, hattip Eddie http://tinyurl.com/2vo5pe4

RT @IceT Me and Coco gotta get more of that global birding, hattip Eddie http://tinyurl.com/2vo5pe4 RT @JackBlackbird Panama's being crazy invaded by huge swarms of birds http://tinyurl.com/32c9m4l

RT @JackBlackbird Panama's being crazy invaded by huge swarms of birds http://tinyurl.com/32c9m4l RT @BirdJoaquin can't get enough of Sweetwater http://bit.ly/a4S6px #DawnFine

RT @BirdJoaquin can't get enough of Sweetwater http://bit.ly/a4S6px #DawnFine RT @Madea I'm having some me time with a big white bird! Gotcha! http://tinyurl.com/25pkl7p

RT @Madea I'm having some me time with a big white bird! Gotcha! http://tinyurl.com/25pkl7p RT @SelmaH nobody digiscopes like the BESG folks, see kingfisher catches frog http://tinyurl.com/25oqoj5

RT @SelmaH nobody digiscopes like the BESG folks, see kingfisher catches frog http://tinyurl.com/25oqoj5 RT @FreakNasty U wanna dip with dis bird? Check out the little dipper http://tinyurl.com/2u22mql

RT @FreakNasty U wanna dip with dis bird? Check out the little dipper http://tinyurl.com/2u22mql RT @JeffGordon despite what you may have heard I'm not new prez of ABA http://tinyurl.com/29zrzxv

RT @JeffGordon despite what you may have heard I'm not new prez of ABA http://tinyurl.com/29zrzxv RT @BirderBeck nothing makes me weep like a good kinglet photo! http://tinyurl.com/3yco32s

RT @BirderBeck nothing makes me weep like a good kinglet photo! http://tinyurl.com/3yco32s RT @Beardchaser thanks for the tip on the shorebirds at Sandy Hook @dendroica http://tinyurl.com/2bg9p73

RT @Beardchaser thanks for the tip on the shorebirds at Sandy Hook @dendroica http://tinyurl.com/2bg9p73  RT @Biebirder dude, check out Corey's kinglets http://tinyurl.com/2e9jubk

RT @Biebirder dude, check out Corey's kinglets http://tinyurl.com/2e9jubk RT @BoratBins I do anything get in next I and Bird. Me too? High five! http://10000birds.com/iandthebird

RT @BoratBins I do anything get in next I and Bird. Me too? High five! http://10000birds.com/iandthebird

Kevin Karlson has posted some photos comparing Chimney and a supposed Vaux's Swift online here. Chimney is on the right, Vaux's on the left.

Kevin Karlson has posted some photos comparing Chimney and a supposed Vaux's Swift online here. Chimney is on the right, Vaux's on the left.  This morning the American Birding Association announced that its board of directors has named my friend Jeff Gordon as its new President. I've known Jeff since I moved to Texas in the mid-1990s. Jeff was working for Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, and brought me on to lead bird tours at the Harlingen Birding Festival. Jeff moved to Delaware shortly after that and I only saw him infrequently for a few years, but it has been fun to spend more time together since I moved out to nearby Pennsylvania. Besides being an expert birder, Jeff is a great human being, with all the organizational and interpersonal skills needed to be a great ABA President.

This morning the American Birding Association announced that its board of directors has named my friend Jeff Gordon as its new President. I've known Jeff since I moved to Texas in the mid-1990s. Jeff was working for Victor Emanuel Nature Tours, and brought me on to lead bird tours at the Harlingen Birding Festival. Jeff moved to Delaware shortly after that and I only saw him infrequently for a few years, but it has been fun to spend more time together since I moved out to nearby Pennsylvania. Besides being an expert birder, Jeff is a great human being, with all the organizational and interpersonal skills needed to be a great ABA President.