2010 was filled with some great birds, though perhaps not as many outstanding birds as the past few years (how can I even dare to say such a thing!). Here are my top 10:

1) Orange-billed Nightingale Thrush. I don't think anyone will ever understand how this bird got from Mexico up to the Black Hills of South Dakota, or the miracle of how it was found singing deep within the trees along a small creek there. But I was happy to hear this bird, and catch a glimpse of it with my kids this summer on our way back from Oregon.

2) Northern Wheatear. Since I've chased and missed this species before, it was a great Christmas Eve present to see this bird in Delaware with my kids. ABA lifer #2 for the year.

3) Tufted Puffin. My kids got to see a couple of these guys flying around Haystack Rock at Cannon Beach, Oregon on our vacation this summer. It's always a good day when you see a puffin.

4) Tufted Duck. I spent fun hour or so watching this bird. I don't get to see too many of these in North America, and it was my first for Pennsylvania.

5) Glossy Ibis. Less than a dozen of these birds have been reported in Utah, so it was fun to find one of these with a flock of White-faced Ibis when I was visiting the inlaws in Cache Valley this summer.

6) Flammulated Owl. Got my best looks ever at these little guys in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah with Bill Fenimore. Super bonus: got to show them to my kids, as well as their cousins and some of my inlaws.

7) Cuervo de los Chontales. A mystery finally solved. Great trip to Mexico.

8) Northern Shrike. Another fun morning, after having missed it once before, spent watching this visitor to my corner of Pennsylvania.

9) Boat-billed Heron. Loved seeing this guy hanging out above a pond in the La Venta museum in Villahermosa, Mexico.

10) Yucatan Jay. Enjoyed seeing these guys in Tucta, Villahermosa. On the edge of their range there, my visit was timed just right to see the only briefly held white juvenile plumage of otherwise black and blue young Yucatan Jays.

Thursday, December 30, 2010

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Banded Snow Goose in NJ

Glad I stopped to scope out a flock of 30,000 Snow Geese on my way to give my final exams at Rowan University last week. Here's what I found out about a neck-collared Snow Goose that I found in that flock. Cool!

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Upcoming Birdchaser Talk in DC

If you are in the DC area, join me next month for this fun presentation.

Friday January 7, 6:45 PM

Pre-Columbian Society of Washington DC January Lecture

“Birds and Bird Lore Among the Ancient and Modern Maya”

Birds have played important roles in Mesoamerican cultures for thousands of years. Rob Fergus explores the connections between birds and various Mayan cultures as revealed in their ancient art and his ongoing field work with seven modern Mayan communities in Guatemala and Belize. In addition to reviewing the role of birds in Mayan writing and iconography, if you want to know how the Turkey Vulture got its red head, which bird you can burn to a crisp to make into a love potion, why you can't have sex before you plant your corn crop, or how to cure warts, this is the program for you!

Sumner School,

1201 17th Street, NW,

Washington, DC

http://www.pcswdc.org/

Friday January 7, 6:45 PM

Pre-Columbian Society of Washington DC January Lecture

“Birds and Bird Lore Among the Ancient and Modern Maya”

Birds have played important roles in Mesoamerican cultures for thousands of years. Rob Fergus explores the connections between birds and various Mayan cultures as revealed in their ancient art and his ongoing field work with seven modern Mayan communities in Guatemala and Belize. In addition to reviewing the role of birds in Mayan writing and iconography, if you want to know how the Turkey Vulture got its red head, which bird you can burn to a crisp to make into a love potion, why you can't have sex before you plant your corn crop, or how to cure warts, this is the program for you!

Sumner School,

1201 17th Street, NW,

Washington, DC

http://www.pcswdc.org/

Wednesday, December 15, 2010

Latest on Birds and Windows

I've been posting about the problem of birds hitting windows for a long time, though not as long as Bill Watterson (see above). Recently I got to spend an afternoon with Dr. Dan Klem who is the leading researcher on this topic. He teaches at Muhlenberg College just up the road from me in Allentown. I've posted an interview with him over at Urban Birdscapes. So if you want to check out the latest on birds and windows, that's the place to be.

birds and bed bugs

Is there a connection between birds and bed bugs? Check out my short article here. While the connection between birds and bed bugs shouldn't be on the top of your worry list, the likelihood of having a problem with bird bugs, while still tiny, is a possibility if you have birds nesting on your house.

Is there a connection between birds and bed bugs? Check out my short article here. While the connection between birds and bed bugs shouldn't be on the top of your worry list, the likelihood of having a problem with bird bugs, while still tiny, is a possibility if you have birds nesting on your house.

Wednesday, December 08, 2010

Hog Island Update

Here's the latest from Audubon about Hog Island. Let me echo the final suggestions here--if you agree that Hog Island is an important treasure as part of Audubon's legacy, then by all means sign up to attend the great programs there and consider donating to make the operations there sustainable. If you are a member of an Audubon chapter, how about making it a tradition to send your Volunteer of the Year up there as a reward each year!

Here's the latest from Audubon about Hog Island. Let me echo the final suggestions here--if you agree that Hog Island is an important treasure as part of Audubon's legacy, then by all means sign up to attend the great programs there and consider donating to make the operations there sustainable. If you are a member of an Audubon chapter, how about making it a tradition to send your Volunteer of the Year up there as a reward each year!*****************************************************************************

Audubon Update on Plans for Hog Island

December 7, 2010

Q: Will Audubon continue to own Hog Island?

A: Yes.

Q: What happens after 2011?

A. Audubon is committed to the ongoing preservation of Hog Island’s biodiversity and wilderness. And we treasure the transformational education and conservation experiences its programs have provided. However, for more than a decade, Hog Island has faced financial challenges related to running and operating residential camp programs, including increasingly high operational costs, shifting consumer travel choices, and changes in the camping industry. That said, we know that Hog Island has many passionate supporters, and we are optimistic that the Friends of Hog Island will be able to develop a sustainable business plan and obtain adequate funding support.

Q. Is there a chance that Audubon would turn over the management of the Island to Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc. or some other entity in the future?

A. At this time, we are committed to seeing if Friends of Hog Island can work with Audubon, Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc. and Maine Audubon to develop a viable business plan and raise the needed money to support the operations and programming on Hog Island. However, if that does not happen, we will continue to explore options with Kieve-Wavus Education.

Q. How long will you give Friends of Hog Island to see if they can raise the support needed?

A. We are in discussions now to determine an appropriate timeline and process.

Q. Why would you work with Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc.? What’s their reputation?

A. We conducted an assessment of potential partners in 2009 and it led us to our current discussions with Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc., a local nonprofit organization whose camps “promote the values of teamwork, kindness, respect, and environmental stewardship” for youth and adults. Audubon and Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc. have been working together informally for more than 30 years, and we have been working more closely together in the past two years. Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc. has an excellent reputation for offering high-quality active-learning educational experiences for young people for the past 85 years. A partnership with Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc. allows Audubon to reach a broader audience, including young leaders. Keive-Wavus Education, Inc. reaches more than 9,000 young people each year. By giving these young people a chance to learn, discover, and explore on Hog Island, we will be helping to build the next generation of conservation leaders. In addition, Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc. has been extremely helpful in ensuring that Audubon’s summer programming last year was successful!

Q. What is Maine Audubon’s role?

A. As mentioned above, Maine Audubon currently manages the buildings and overall upkeep, and they will be transferring those management responsibilities back to National Audubon. (They took over management of the Island in 2000.) Maine Audubon will be working with Kieve-Wavus Education, Inc. to integrate environmental education into Kieve’s programming. In addition, Maine Audubon will continue to work with Audubon to support high-quality programming on the Island.

Q. How can other supporters of Hog Island help?

A. There are many ways you can help support Hog Island.

The first is to sign up for programming. We want to make sure that all sessions are full, enabling us to meet our programming and financial goals for the season. For more information, visit http://www.projectpuffin.org/OrnithCamps.html

The second thing you can do is to provide financial support for the Island’s operations and programming. We need funding to support the operations and the development of an endowment. In addition, we need funding to support building upkeep and upgrades to allow for continued programming. If you are interested in donating to Hog Island, please visit https://loon.audubon.org/payment/donate/PUFFHOGISL.html Even small amounts can add up to make a huge difference. And finally, you can volunteer on the Island, working with Friends of Hog Island and Audubon staff to help prepare the camp for programs.

Audubon looks forward to working with everyone who is interested in the future of Hog Island. And if you have questions, please email jbraus AT audubon.org.

Friday, December 03, 2010

Field Guide to Cartoon Birds

Original Cocoa Puffs Cuckoos

I didn't realize that Sonny was only one of two original Cocoa Puffs cuckoos--once upon a time Sonny was paired with Gramps. Question--are Cocoa Puffs made with bird-friendly cocoa?

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Crazy Geese

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Peace Valley in the wind

Quick stop at Peace Valley this morning, in the high winds, produced the following migrants:

Red-throated Loon (1)

Red-necked Grebe (2)

Greater Scaup (1)

Black Scoter (1)

Bufflehead (12)

Ruddy Duck (5)

All were out too far for any effective digiscoping.

Red-throated Loon (1)

Red-necked Grebe (2)

Greater Scaup (1)

Black Scoter (1)

Bufflehead (12)

Ruddy Duck (5)

All were out too far for any effective digiscoping.

Friday, November 12, 2010

Fountain Hill Hummingbird

Spent an enjoyable morning visiting with Ed Sinkler, Arlene Koch, and Dennis Glew while waiting for and occasionally watching the female Selasphorus hummingbird in Fountain Hill, near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The bird is thought to be a female Rufous Hummingbird, but hopefully that will be confirmed when Scott Weidensaul stops by to band it this afternoon. Ed noticed the bird at the hummingbird feeder in his back yard earlier this week, and welcomes visitors to his backyard to see the bird. You can just walk up the paved walkway along the right side of the house to the back where there are chairs set up where you can watch the two feeders. Make sure to sign the guestbook.

Spent an enjoyable morning visiting with Ed Sinkler, Arlene Koch, and Dennis Glew while waiting for and occasionally watching the female Selasphorus hummingbird in Fountain Hill, near Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The bird is thought to be a female Rufous Hummingbird, but hopefully that will be confirmed when Scott Weidensaul stops by to band it this afternoon. Ed noticed the bird at the hummingbird feeder in his back yard earlier this week, and welcomes visitors to his backyard to see the bird. You can just walk up the paved walkway along the right side of the house to the back where there are chairs set up where you can watch the two feeders. Make sure to sign the guestbook.Photo: Howard Eskin (more here)

Thursday, November 11, 2010

Prepare Now for Turkey Day

In our family, Thanksgiving is Turkey Day. Since 2004, I've been taking the kids out each Thanksgiving to look for Wild Turkeys before the food festivities. In fact, the 2004 chase was my very first Birdchaser post!

Some years we find the birds, sometimes we don't. But every year it is an adventure, and a great way to celebrate the natural world. Back in the early 1900s, there were only 30,000 Wild Turkeys running around out there. Now there are over 5 million of them. So Wild Turkeys can symbolize the hope we have for restoring and protecting our native birds, and the rest of our natural heritage.

Celebrate Turkey Day by taking someone you love out to look for Wild Turkeys where you live. If you don't have turkeys in your area, you can substitute some other cool (preferably gallinaceous) bird. And it will be more fun if you can actually find them, so now is the time to start scouting out local turkey haunts so you can get in the same groove as your local turkey flock.

Have fun and let me know how it goes :-)

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

Tuesday, November 09, 2010

Steve Martin on shooting The Big Year

Steve Martin was on Letterman talking about shooting The Big Year (see discussion from about 2:25-5:05).

(Hat tip: John)

(Hat tip: John)

Monday, November 08, 2010

Barry White--Serious Bird Lover

Found this 1979 Ebony article where crooner Barry White talks about his love for air (birds), water (fish), and earth (horses). At the time of the interview he had a 480 gallon saltwater aquarium, $1.5 million in horses, and birds including cockatoos.

Found this 1979 Ebony article where crooner Barry White talks about his love for air (birds), water (fish), and earth (horses). At the time of the interview he had a 480 gallon saltwater aquarium, $1.5 million in horses, and birds including cockatoos. So, Barry White. Bird Lover. Who knew?

Anybody know any good Barry White bird tunes?

Helping Audubon Help Birds

Last week I made some very critical remarks about the national Audubon organization and some of its historic and organizational struggles. While I made every effort to be sincere and to make sure that what I posted was accurate, there is still a problem with what I posted.

Last week I made some very critical remarks about the national Audubon organization and some of its historic and organizational struggles. While I made every effort to be sincere and to make sure that what I posted was accurate, there is still a problem with what I posted.According to German sociologist and philosopher Jürgen Habermas's Theory of Communicative Action, effective communication requires three essential elements--

1) It must be truthful

2) It must be sincerely conveyed

3) It must conform to accepted social rules

The third point is where I failed. I was critical and somewhat intemperate in my remarks. My tone was more attacking than conciliatory. Some of my intentions were clouded over by my passion, and my posts were not the most effective way to strengthen Audubon and the bird conservation community.

Since my original intent was to protest the possible loss of Hog Island as a center for building and sustaining a national Audubon community, to the extent that my posts offended or turned off members of that community with the power to influence that decision, then my posts failed in their attempt. To the degree that the posts could be taken as a Jerry Maguire moment, I lost credibility as a rational and viable partner and valuable member of that larger Audubon community. So my posts have failed to some degree, and my posts have damaged my relationships to people I care deeply about within the Audubon community. I feel that intensely, and feel the need once again to apologize.

In my best moments, my intent is to strengthen and support the Audubon societies as the strongest and potentially most effective bird conservation organizations at the national, state, and local level. I hope to my previous comments can be charitably read within that context and not as an attack on Audubon or any member of the Audubon community.

We are at a critical time in the history of Audubon. Birds need our help. The economy has financially weakened nonprofits across the country. National Audubon has a new president, which usually leads to shifts in policies and priorities. There is a lot of work to do, and it will take all of us who care about birds and/or Audubon to get this work done.

So here's my take on how you can help Audubon help birds.

1) Join Audubon. In many places you can join at both the National and the local level. National Audubon needs your support. So does your local chapter. So depending on how Audubon is organized in your area, determine if you have the opportunity to join at both the national and local chapter level.

2) Crack the Wallet. You can give to Audubon at the local, state, or national level. You can provide general support (there are always light bills to be paid), or you can support individual programs that you are most interested in. Take a look at what Audubon is doing on each of these levels, and see where you want to put your dollars to work. Since there is a lot to do, and a lot going on, there are a lot of programs and projects to support.

3) Be a Leader. If you care about birds, don't just get involved--take on a project with your local Audubon chapter. What do birds need in your area? You and a couple other people can form a subcommittee and take on the world. If you'd rather just spend your time birding, go back to suggestion number two and at least make it financially possible for someone else to do the important conservation work while you enjoy your time birding. Audubon even has some funds available that can help you do your local projects. You can also become a leader on the state level by getting involved with a statewide Audubon council linking the chapters in your state, or by serving on the board of your statewide Audubon organization. There are also ways to be involved on the National Audubon board. But you don't have to have a title or position to be a leader. If you care about birds, lead out on whatever it is that you see needs to be done.

4) Be a Follower. Even more than financial support, what good leaders need are good followers. Do what you can to support your local Audubon chapter leaders. Ditto for your statewide and national Audubon officers and staff. You may not always agree with everyone, but do your best to work through your issues without rancor. If you're reading this post you know that I haven't always succeeded here. But I am dedicated to keep trying. To patching up difficulties so we can work together. We have enough obstacles and sometimes even enemies to face without having to worry about getting stabbed in the back by members of our own community while we are out trying to do our best. Sometimes there is a tendency to complain and take our marbles elsewhere when we are upset. We need to practice following sometimes, even when we disagree, for the benefit of the larger good. This is something that seems to be breaking down in some sectors of our larger society. It is a tough skill for some of us to develop. But remember that united we stand, divided we fall. We've already seen a lot of falling in the bird world, and perhaps the greatest threat that Audubon and the conservation community face right now.

5) Be heard. Make your wishes and desires known within Audubon at all levels. Remember what it takes to be an effective communicator (truth, sincerity, living by the rules of the group with which you are communicating). Clean up your messes when you make them, but be in communication. On my best days I know that my messages have the greatest influence when they persuade with patience, gentleness, meekness, and love.

6) Have Fun. Sometimes we think birding is fun, while bird conservation is work--the last thing we want to do after a full day or week at the office. So make it fun. Make sure you have lots of fun meetings--with food. Get involved with people you enjoy being with. Let the creative juices flow. Plan bird conservation parties. Contests. Competitions. And more parties. If you have the best parties in town, you will get the most done!

7) Go to Hog Island. Along the lines of having fun, attend Audubon's chapter leadership workshops (next one is Aug 15-20, 2010) or other programs on Hog Island, Maine. Soak in the sights, sounds, and legacy of this traditional Audubon stomping ground. Take the boat out to see the puffins nesting on Eastern Egg Rock. Enjoy the great food. Hang out and share your best Audubon thoughts with like-minded local Audubon folks from around the country. If each Audubon chapter sent one member to this camp each year, we would need 10 camp sessions so the future of the camp would be financially secure, and we would be much stronger as a national community--a true Audubon society!

Yes we have our problems and squabbles within Audubon, most of which are probably not best addressed through blog posts. Audubon is a big tent, a tent that both needs and can provide support and opportunities for all of us. Under that tent we will strengthen each other and our cause as we all work together to conserve and restore natural ecosystems, focusing on birds and other wildlife for the benefit of humanity and the earth's biological diversity.

Monday, November 01, 2010

Why I Love Audubon

As hopefully a final post in this recent series on birds and Audubon, I'd just like to highlight some of what I really love about Audubon. Mostly people who are doing great work, some of which you may not have heard of. There are thousands of them across the country, passionate and effective Auduboners at the National, State and local chapter level. Here are just a few:

As hopefully a final post in this recent series on birds and Audubon, I'd just like to highlight some of what I really love about Audubon. Mostly people who are doing great work, some of which you may not have heard of. There are thousands of them across the country, passionate and effective Auduboners at the National, State and local chapter level. Here are just a few:1) Stephen Kress. For decades, against all odds, Dr. Kress has put together one of the most effective bird conservation programs in Audubon. He has brought puffins and nesting terns back to the coast of Maine, and has solid data to show the effectiveness of his work. He has trained hundreds of young interns over the years, and his work is an inspiration for similar projects around the world.

2) Paul Green. After serving as the president of the American Birding Association, and then as the Director of Citizen Science for Audubon, Dr. Green moved to Tucson where he heads up the Tucson Audubon Society and its groundbreaking efforts to protect the birds of Southeastern Arizona, including a landscape design course for homeowners and landscape professionals.

3) Stephen Saffier. I worked with Steve in Audubon's Science Office, and now he heads up efforts to create communities and neighborhoods that are good for birds and people at Audubon Pennsylvania. Instead of getting mired in the politics of Audubon, he has been able to implement some of the best ideas we ever had, including a backyard bird conservation program and a database linking birds to the native plants that they use and that people can plant to support them.

4) Jane Tillman. When I was at Travis Audubon Jane took on leading an Urban Habitat Committee that works tirelessly to make Austin better for birds and people. Jane and her committee have undertaken many local projects over the years, including creating backyard habitats and installing Chimney Swift towers in local parks.

5) Brian Rutledge. I love Sage Grouse, and Audubon is definitely stronger for having Brian Rutledge (Audubon VP of the Rocky Mountain Region) and his crew working tirelessly to protect them from environmental threats including damage done by extensive energy development in Wyoming.

6) Stella Miller. When Huntington-Oyster Bay Audubon president Stella Miller heard that hundreds of hawks and other birds of prey were being seriously injured by methane burners at landfills and other industrial facilities, she didn't just wring her hands in despair. She took on the challenge and is working with industry groups to bring this issue to their attention and put in measures to protect the birds.

There are thousands of people in Audubon that are just as effective and passionate as these examples. I will be highlighting each of these, and many more, here and on my Urban Birdscapes blog. Audubon is well served by these people, and will be well served by supporting them and giving them the resources they need to be effective in protecting the birds and habitats we share with them.

Saturday, October 30, 2010

Jon Stewart's Medal of Reasonableness

Friday, October 29, 2010

First Social Flycatcher in the US?

This week I visited The Research Museum at the Acopian Center for Ornithology at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Their bird collection was in storage for many years, but in going through and curating their collection, they found this Social Flycatcher, collected in Brownsville, Texas in February 1887. This should represent the first Social Flycatcher record north of Mexico. Unfortunately there isn't a lot of data associated with some of these old specimens, but the record has been submitted to the Texas Bird Records Committee.

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Bird Hazard Survey

What hazards are killing birds? How does our society deal with these hazards?

What hazards are killing birds? How does our society deal with these hazards? Yesterday I was up visiting researchers at Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pennsylvania who are looking at some of these issues. They are requesting that people help them study these types of questions by filling out an online survey.

Many birds are killed each year by various forms of human technology and activity. Some of these human-made hazards attract much more attention than do others. The researchers are interested in how various factors shown to influence people’s perceptions of the risks posed by nuclear power or water pollution (e.g., is it a ‘new’ hazard, how 'natural' does the hazard seem) may also contribute to peoples’ perceptions of various hazards to birds. This information will be useful in helping bird conservationists strategize in campaigns to raise awareness with regards to different kinds of threats to birds and other natural systems.

Please fill out the survey found at the following link: http://www.zoomerang.com/Survey/WEB22BDFEUJWXT

Your participation will remain anonymous and confidential. The survey takes about 25 minutes to complete. At the end of the survey, you will be re-directed to a separate page upon which you can request a summary of what we find. This research project has met Muhlenberg College’s Institutional Review policy requirements.

If you have any questions about the project, please do not hesitate to contact Dr. Jeffrey Rudski at rudski AT muhlenberg.edu.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Real UK Birdwatching Celebrities

Here's a recent list from the BBC's Stephen Moss. Heavy emphasis on the BRIT in celeBRITy here, no mention of American birdwatchers including Jimmy Carter, Laura Bush, Jane Alexander, Wes Craven, or Daryl Hannah.

Here's a recent list from the BBC's Stephen Moss. Heavy emphasis on the BRIT in celeBRITy here, no mention of American birdwatchers including Jimmy Carter, Laura Bush, Jane Alexander, Wes Craven, or Daryl Hannah.Here's more on UK birdwatching celebs.

Future of the ABA--in 1996

Rummaging around in my files this afternoon, I found a copy of a letter that I sent to then American Birding Association president Greg Butcher back in 1996. I had searched for this letter a couple months ago, but it didn't turn up until today. At any rate, back in 1996 I had been working seasonal bird jobs for a few years out of college, had helped launch the Great Texas Birding Classic, and I was a young guy with a lot of ideas. So I wrote some of them to Greg, who I had met while planning a 1996 North American Big Year fundraiser for Audubon that didn't happen, and the Great Texas Birding Classic, which was about to happen.

Anyway, here's the letter:

A few of these ideas seem a little strange now, but I'm surprised how many of them were actually accomplished by the ABA since then (Junior Audubon notebook contest, Lane birdfinding guide for birding in American cities, etc.). Perhaps I wasn't the only one to suggest these ideas, but at least it is nice to see that my ideas had wings. There might even be some old ideas here that are still worth pursuing. And as always, there are many more ideas where these came from!

Anyway, here's the letter:

A few of these ideas seem a little strange now, but I'm surprised how many of them were actually accomplished by the ABA since then (Junior Audubon notebook contest, Lane birdfinding guide for birding in American cities, etc.). Perhaps I wasn't the only one to suggest these ideas, but at least it is nice to see that my ideas had wings. There might even be some old ideas here that are still worth pursuing. And as always, there are many more ideas where these came from!

Friday, October 22, 2010

Review: The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America

The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America is a colossal wonder. As advertised, it has:

The Stokes Field Guide to the Birds of North America is a colossal wonder. As advertised, it has:--More photos (3,400) than any other North American field guide

--More species (854) than all but the National Geographic field guide

--More subspecies (all) included than any other North American field guide

--More hybrid combinations than any other guide (all reported hybrids included)

--American Birding Association finding codes (only the Smithsonian Guide also includes these)

--Most recent changes to scientific names and recent species splits including those announced this summer, like Pacific Wren

It also features:

--Way more pages (816) than any other North American field guide

--More weight (3 lbs) than any other North American field guide, including Big Sibley

Don and Lillian Stokes spent more than six years putting this guide together, and it shows. It is a monumental work. Birder's World magazine posted a must-read interview with the Stokeses, which provides a detailed look into the decisions that the Stokeses made in order to make this guide, as outlined in the guide's preface, "the most useful guide to identifying the birds of North America ever published."

That's a tall order, but the true measure by which this guide invites us to evaluate it. So how are we to determine the usefulness of a guide like this? Or determine which guide might be the most useful? That's perhaps an equally tall order, one that I'm hesitant to tackle, but one which I find unavoidable in attempting to provide this review.

Any question of usefulness should look at how the book is actually used by possible intended audiences. We'll have to leave that for a future review, as I have not yet field tested it with others. For now I can only speculate about how the book might be useful to others. I will do a little speculating here, but mostly look in more detail at how useful I find it for me personally.

I would love to hear how useful beginning birders or casual birders find this guide. 800 pages and 3400 photos are a lot to thumb through in order to find an unfamiliar bird. At 3 lbs, some reviewers have already mentioned that they probably wouldn't carry it around in the field. Most intermediate and advanced birders don't carry guides in the field, but may carry one in their car. Otherwise, field guides are usually references or perhaps armchair guides--useful for looking up field marks on unfamiliar birds, or for studying before heading out in the field. Again, I would be interested to hear more about how this guide is actually used by beginners and more advanced birders.

For me personally, the question of usefulness boils down to questions like these:

1) Is this the guide I would most likely carry with me in my car for regular birding?

2) Is this the first guide I would look if I needed to look up something unusual after coming back home from the field?

3) Is this the first guide I would look at to review birds I haven't seen for a long time before heading on a trip to somewhere I don't get to very often?

4) If I could only take one field guide with me on a cross country trip, would this be the one?

I'll leave off the suspense and just state that for now, the answer to all of these questions is probably no. As useful and great as this guide is, and as much as I think I will refer to it in the years to come, I don't see it as my first "go to" guide. Here's why:

1) Photos: I've already outlined the problems with photo guides in another review, so I don't want to totally rehash those points here. While the photos in this Stokes guide are for the most part outstanding, I don't find presentations of photos to be the best way to quickly and easily identify birds, or to review the finer points of bird identification. They are great for reference, but I find it easier and more useful to have similar species depicted next to each other, with diagnostic points enumerated on the illustrations, perhaps with supplemental diagrams. In the Birder's World interview, the Stokeses tell us why they didn't want to clutter up their photos with text describing field marks, and they are right that it detracts from the beauty of the photos, but in a field guide, and especially in a beautiful one such as this, a focus on aesthetics may come at the cost of some utility.

2) Comprehensiveness: I'm glad that the book covers 854 species. That is more than Sibley (810) and all of the other field guides except for National Geographic. All regularly occurring wild birds (ABA finding codes 1-4) are included, as well as many birds that have only shown up a few times in North America. It is fun to see multiple photos of such rarities as Great Frigatebird, Lesser Frigatebird, Brown-chested Martin, and Common Redshank. But for a traveling urban birder like me, I'm more likely to have to identify a host of free-flying exotic species including parrots and waterfowl that are well-covered in other guides, but not included here.

One of the goals of this guide is "to create the most complete photographic record of...plumages and subspecific variations that has ever existed in one guide" (from the preface). The Stokes guide clearly does this. But just because it is the most complete photo guide doesn't make it the most complete field guide--illustrated guides often provide more images of each species, including more illustrations of subspecies, plumages, and birds in useful positions including flight images. Here's a quick comparison of the Stokes guide to the NWF and Smithsonian photo guides and Big Sibley (an illustrated guide)--using random birds that just pop into my head.

Each of these guides has its own strengths and weaknesses on the images front. Stokes clearly is the most complete photo guide, but far from the most complete guide, and even misses some photos that you would expect (like juvenile owls) or want (flight shots for most songbirds). Interestingly, Stokes was the only one of these guides to illustrate a baby Mountain Quail. None of these guides, including Stokes, illustrates most baby game birds. Or shortly-held juvenile plumages for most songbirds. We have yet to see those included in a standard field guide.

As far as including subspecies, Stokes does mention all subspecies and provides a shorthand description of their range and distinguishing marks. Most are not illustrated. While the guide may be a useful indicator for noting subspecies identity of birds within their known geographic ranges, it usually won't be enough information to actually identify an out of range individual to the subspecies level--that would take a more detailed reference. Interestingly, some species rarely seen in North America (like Green Violetear and Green-breasted Mango) are illustrated (and clearly labeled) with individuals of subspecies not found in North America.

3) Text: There is a lot of text here! That is good (for providing information) but can be tough to sort through--again perhaps making it more useful as a reference than as a field guide for making quick IDs. Each species account provides several sections, each labeled with red or black bold section markers, which does chunk the information and make it easier to find. Sections include an initial description of each bird's shape, then descriptions of each plumage--usually of birds both sitting as well as in flight, a short line on habitat, and a voice description of commonly heard vocalizations. This is followed by the list and brief description of each subspecies, as well as a list of known or reported (as well as suspected) hybrids.

One feature that the Stokeses have tried to advance, is a more quantitative measure of bird shape--especially expressed as rations of one body part to another. Sometimes this is very useful--as in comparative bill to head lengths--while other times maybe not so useful--how easy is it to determine that a Buteo hawk's wing length is 2 1/4, 2 1/3, or 2 1/2 of its wing width?

The text of the Stokes guide does a much better job than most photo guides of comparing birds to similar species and providing distinguishing field marks. That said, much of the species descriptions are still that--just descriptions without highlighting plumage features that separate them from similar species. I generally find it more useful to have one species described by comparing it directly with another. So while there is nothing wrong with, for example, describing the Ringed Kingfisher by listing the various color features of its plumage, including that its tail is barred black and white--it might be more useful for some birders to have the bird described in comparison to the common and for most of us more familiar Belted Kingfisher or to focus on those features which are clearly distinctive. In short, I miss the Similar Species section of the old Peterson guides.

So suppose I'm in my car with my scope on my window mount and I think I've got a Bar-tailed Godwit out on the mud flats. I want a quick review of how to make sure. It doesn't fly, so I can't see its rump. I open up Stokes to the Bar-tailed Godwit account. Dang! There's six photos there, lots of text. I struggle to wade through it all to figure out what exactly would make it a Bar-tailed Godwit rather than a Hudsonian Godwit three pages away. Or maybe it is a juvenile Marbled Godwit? Wait, there is no photo of a juvenile Marbled Godwit. Hmmm. Where's Big Sibley? All four godwits in a row in Big Sibley. I quickly compare them and feel much better about my initial identification.

Don't get me wrong. The Stokes guide provides lots of useful information. Tons. It's just that between all the details in the text, and the vagaries of the beautiful photos, it doesn't always provide the information I want in the easiest format for me to quickly use, especially in the field.

But again, tons of useful information here. In many cases, the text descriptions may actually make it easier to age and sex an individual of the species, than to distinguish it from a similar species. For birders who want to age and sex individual birds, this information is useful. For birders who just want to identify a bird to the species level, the information here might be a lot to wade through--especially if there are no comments clearly outlining distinctive features or comparing similar species.

I need to reiterate that there is a LOT of text here. The Red-tailed Hawk account is well over a thousand words (I gave up trying to count!) and includes the equivalent of almost one and a half full pages! For hawkwatchers, there are lots of tips about identifying birds in flight, but not as many illustrations as in Big Sibley. This is a bit frustrating in the case of Accipiters, as the similar Sharp-shinned and Cooper's Hawks each get more than a full half page of text, but only six photos each. It is nice to have them on adjacent pages for comparison, but I'm not sure that the chosen images really provide enough information for most birders to use them in attempting this common but tricky identification challenge based on the subtle features mentioned in the text.

Maybe it is unfair to review a guide based on the more difficult identification challenges out there. Perhaps those identifications are best left to comprehensive specialty guides, in this case something like Liguori's Hawks from Every Angle or the classic Hawks in Flight, where subtle marks can be given more discussion and space for illustration. This example merely illustrates how tough it would be for any guide to be the "most useful" in any given situation.

4) Maps: I haven't gone through the maps with a fine tooth comb, but they seem to be accurate and up to date. The color scheme is familiar to old timers who cut their teeth on the old Golden Guide, with red summer ranges, blue winter ranges, and purple permanent ranges. Migration routes are marked with bright yellow (rather than the old hashed shading of the Golden Guide). Areas where out of range birds are known to wander are enclosed in yellow, red, purple, or blue dotted lines--which gives some indication of where wanderers may occasionally appear. One thing that I really liked in the Kaufman guide when it first came out were the light and dark shading to indicate relative abundance across a bird's range. Neither the Stokes guide, nor any other major guide, has kept up with that innovation.

There's a lot more to talk about, perhaps here in the comments section, including the associated CD of bird sounds and mini Identification Tips essays on how to ID some groups of birds like hawks, shorebirds, and gulls. Speaking of gulls, there is a lot of information on gulls here--full two-page spreads for most larger 4 year gulls. Again, this is more than found in most guides, situating the book halfway between a standard field guide, and a more detailed reference guide.

In the end, that is where this book seems to settle with me--as a bridge between field guides and more detailed reference guides. Perhaps it is most useful in that way--in the car as a stepping stone between checking in a field guide and a reference book at home. So while it wouldn't be the first book I would carry in my car (that one still goes to Big Sibley for me, Kaufman for the kids), it might well be my first choice to ride in the car as a backup to consult before checking more references back at home.

So, in summary, the Stokes guide probably really is, as advertised, "the biggest, most colorful" guide out there. As for being the most useful, I've discussed how that probably isn't the case for me, but I am enjoying other reviews online, and am interested in hearing how the book fares with the larger birding community and individual birders across a wide spectrum of interest and abilities.

Like all guides, it has its strengths and weaknesses, some of which I've pointed out. Perhaps more than most field guides, the Stokes guide is like a box of chocolates--when you look in there to identify a bird you are not always sure what you are going to get. Beautiful photos for sure. Lots of text to read. Maybe a fantastic nugget of useful info. Sometimes not as much as you might like.

But I'm a big chocolate fan, and this is a seriously big and beautiful box of chocolate. So it's a keeper and I look forward to dipping into it for years to come.

This review is written on the basis of a review copy provided by Little, Brown and Company.

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Surprise AC/DC Birding Lyrics

SYDNEY (AP) —A new museum exhibit about Australian rock band AC/DC makes some startling revelations, including that the anthem "For Those About to Rock (We Salute You)" was originally written during the 1980 Christmas Bird Count season to celebrate birding. According to the original draft (see copy below), the lyrics were considered too nerdy and were changed for release the next year on the groups 8th studio album.

As originally written, the song urged all birders to stand up and be counted, and was originally performed in Maryland after a Christmas Bird Count, when birdwatchers who have been out counting birds all day gather together to make a list of all the birds they've seen during their annual all-day bird count.

Here are the lyrics as originally written and performed:

Oh Yeah, yeah

We roll tonight

To the birds in flight

Yeah, yeah, oh

Stand up and be counted

For all the birds that you have seen

We are the birders

We are birding lean and mean

Hail hail to the good times

'Cause birding's got the right of way

We ain't no legend, ain't no cause

We're just livin' for today

For those about to bird, we salute you!

For those about to bird, we salute you!

We bird at dawn on the front line

Like a bolt right out of the blue

The sky's alight with birds in flight

Birds will roll and flock tonight

For those about to bird, we salute you!

As originally written, the song urged all birders to stand up and be counted, and was originally performed in Maryland after a Christmas Bird Count, when birdwatchers who have been out counting birds all day gather together to make a list of all the birds they've seen during their annual all-day bird count.

Here are the lyrics as originally written and performed:

Oh Yeah, yeah

We roll tonight

To the birds in flight

Yeah, yeah, oh

Stand up and be counted

For all the birds that you have seen

We are the birders

We are birding lean and mean

Hail hail to the good times

'Cause birding's got the right of way

We ain't no legend, ain't no cause

We're just livin' for today

For those about to bird, we salute you!

For those about to bird, we salute you!

We bird at dawn on the front line

Like a bolt right out of the blue

The sky's alight with birds in flight

Birds will roll and flock tonight

For those about to bird, we salute you!

Tuesday, October 19, 2010

Birdchaser Interview: Attuvian John Puschock

John Puschock is a Seattle-based bird tour leader and owner of Zugunruhe Birding Tours, which offers tours to far-flung birding hot spots including the fabled Attu Island in the Aleutians. I've been dreaming about going to Attu since the early 1980s, when I first read about it in James Vardaman's classic recounting of his 1979 North American Big Year Call Collect, Ask for Birdman. In 1995, when I was planning my own North American Big Year as a fundraiser for Audubon (but that's another story), I actually paid the $300 down payment for a spring trip to Attu, but when Audubon pulled its support for the venture and I lost that deposit and a few years later Attour closed down its trips. It looked like my chances of getting to Attu, and seeing dozens of cool Siberian vagrant birds in North America, were gone for good. A few years ago Victor Emanuel Nature Tours stopped by Attu, and last year Zugenruhe started offering boat-based trips there again. So perhaps I can still get out there yet!

John Puschock is a Seattle-based bird tour leader and owner of Zugunruhe Birding Tours, which offers tours to far-flung birding hot spots including the fabled Attu Island in the Aleutians. I've been dreaming about going to Attu since the early 1980s, when I first read about it in James Vardaman's classic recounting of his 1979 North American Big Year Call Collect, Ask for Birdman. In 1995, when I was planning my own North American Big Year as a fundraiser for Audubon (but that's another story), I actually paid the $300 down payment for a spring trip to Attu, but when Audubon pulled its support for the venture and I lost that deposit and a few years later Attour closed down its trips. It looked like my chances of getting to Attu, and seeing dozens of cool Siberian vagrant birds in North America, were gone for good. A few years ago Victor Emanuel Nature Tours stopped by Attu, and last year Zugenruhe started offering boat-based trips there again. So perhaps I can still get out there yet!I first met John Puschock back in 2006 when I was out in San Diego. I found a locally rare Marbled Murrelet off La Joya Cove, and John was one of the incredulous birders who showed up to look for it for several days before it was rediscovered and my sighting was vindicated. The funniest thing I remember about hanging out with John at La Jolla Cove was when I asked if I could borrow his scope, and he said I could as long as I didn't have pink eye. Funny guy!

Anyway, I've kept up with John off and on over the past few years, and am happy to have him join me on here for a Birdchaser Interview:

BIRDCHASER: So, when we met back in 2006, were you already leading tours then?

JP: First off, if the line about the pink eye was the funniest thing you

remember, I must have been having an off day. Sorry about that ;-)

And yes, I started leading tours in 2004 for Bird Treks, and when I moved to San Diego in 2005, I also began a business doing day trips around southern CA. I’ve since moved to Seattle and started Zugunruhe Birding Tours, but I still work for Bird Treks, too. But I’ve dropped the San Diego day trip portion of the business since the commute was a killer.

B: How did you start going to the Aleutians?

JP: The long version of the story begins with me not seeing a Gray-headed Chickadee, at least not definitively, while working in northwest Alaska in 1998. But no one wants to read a long story on a blog...The short version is I read Ted Floyd’s account of his trip to Adak in Aug 2003 and that the island was becoming accessible to the general public, so I asked Bob Schutsky, owner of Bird Treks, if he’d be interested in working with me to develop a tour there. He said yes.

B: What have been some of your best birding experiences on Adak?

Literally at least ten things come to mind, but I’ll try to pare it down...Every time we go out on a boat to look for Whiskered Auklets is special. I’ve seen quite a few now, but it’s still a mythical bird to me. Seeing one just twenty feet away never gets old.

I’ve seen four Marsh Sandpipers on Adak, and those were all great. The last two were together, and I had seen one a week earlier when I didn’t have a group with me. I told the tour participants about that bird (the one I saw by myself) before they got there, and that I didn’t expect it to stick around long enough for them to see it. I was right about that, so finding another two while my group was there more than made up for that – snatching victory from the jaws of defeat added to the excitement.

But my favorite experience was finding an Eastern Spot-billed Duck. It was late in the day, probably 9 PM, and unfortunately I didn’t have a group with me at the time – I had stayed a few extra days after my group had left – so I was driving around Clam Lagoon by myself. I surprised a group of Mallards near the road, and they all jumped. I put my binoculars on part of the group flying away and thought to myself, “That one looks different.” It landed, I got a quick scope view, and I was soon flying down the road back to town to get the other birders on the island. Some of them were already in bed, but everyone came out for it.

B: How did you end up deciding to do trips to Attu?

JP: I’ll go with the short version again: I found a boat that was close enough to Adak to make the trip financially feasible. I know a few others had tried to get there since Attour closed up shop, but the stumbling block always was finding reasonable transportation. The closest appropriate boats had been in southeast Alaska, and the cost of getting them to the Aleutians was prohibitive. Luckily, I found out about a boat, the Puk-Uk, in Homer.

B: There was a serious Attu birding culture and community that developed around Attour. Are you getting some of those old Attuvians coming back now on your tours?

JP: I had one Attour Attuvian on last year’s trip (our first), two who were on the VENT trip in the fall of 2006, plus one of my guides, Mike Toochin, was an Attour guide throughout the 90s. Now that we’ve proved we can do the trip and I’ve been able to drop the price too, I’m hoping some more will join us. I’ve always been interested in the history and tradition of birding, so it would be great to hear stories about the old days.

B: How are trips to Attu different now than they were back in the glory days of Attour?

JP: We sleep and eat on the boat now, not the old buildings that Attour used. Those building are still there, by the way, along with everyone’s list totals written on the walls. There are fewer people on our trip, but otherwise I think it’s pretty similar. We have bikes to get around, and it’s still windy.

B: Given that some years are better than others, what should a birder expect to be able to see on your Attu trips?

That’s a tough question if you’re asking about Asian vagrants. Last spring, the Aleutians were plagued with north winds for weeks. That’s not the direction you want the winds to be blowing for vagrants, and we did miss some that I thought were a sure thing: Lesser Sand-Plover and Common Sandpiper come to mind. We also had low numbers of Wood Sandpipers (3) and Long-toed Stint (1). But we did get other “expected” species such as Rustic Bunting and Brambling, plus other less-expected species like Hawfinch, Red-flanked Bluetail, and the bird of the trip, the first accepted North American record of Solitary Snipe. Of course, the species normally resident in the Aleutians and Bering Sea would be expected. We saw tons (probably literally) of alcids, included Whiskered Auklet. We saw every seabird expected and not-so-expected in the area, including Short-tailed Albatross, Mottled Petrel, and Red-legged Kittiwake. The bottom line is that a birder can expect to see vagrants and other cool birds that can't be entirely predicted, though the Whiskered Auklets are very likely.

B: Can birders see as many birds on Attu with these smaller groups as they did back in the day when there were larger groups potentially covering more parts of the island?

JP: I’m sure we’ll miss a bird here and there with our smaller group, but I think we’ll get most of them. For a long time, I thought you could only bird the island with a large group, but then the thought occurred to me that Univ. of Alaska-Fairbanks has been sending a team of two to the island for years to collect specimens, and they’ve been turning up good birds all the time. If two could do that, certainly ten could do even better.

BP: For the cost of an African safari, why should someone bird Attu or the Aleutians? What makes the Aleutians, and Attu in particular, so special?

I’m not going to tell anyone they should bird the Aleutians. Everyone has different interests. Even among the Attour crowd, people came for different reasons. From what I’ve heard, there were even a few who weren’t birders. But I will say why someone might enjoy it:

The Aleutians are a corner of the world that’s unlike anywhere else and almost certainly completely different than where you live. In that respect, it’s the same as an African safari or any other exotic location. It’s wild and remote. It’s an expedition. I like the excitement of not knowing what I might find...and then the excitement of finding it. And while Attour was finding all those first North American records, Attu was elevated to legendary status among birders, so there’s that aspect to it, too -- walking around Lower and Upper Base (where Attour used to stay) was like being in a shrine. Of course, if you want to pump up your ABA list, there’s no better place to go, particularly if it’s your first visit to the Bering Sea region.

There’s always that cost-per-bird issue with trips like this (and implicit in your question). If you’re a world birder, particularly if you’ve already seen the Beringian endemics like Whiskered Auklet and Red-legged Kittiwake, and your interest is getting more life birds, frankly there’s no reason to go to Attu. But if you’re into your ABA list, then this trip makes more sense, especially if you haven’t been to Alaska before. It would save having to make a separate trip for the Auklet, plus you may see all the resident species you would see at St. Paul, possibly saving a trip there (though admittedly the experiences would be different – at St. Paul you get to see the seabirds from close range while both you and the birds are on land).

I like to do trips that go beyond just ticking off lifers and are about the quality and/or uniqueness of the experience, and this is one of them. As an aside, I just got back from a tour that was my favorite ever – great birds, great people – and the trip list was only 19 species. No lifers for me, but among the 19 were Ross’s and Ivory Gulls, Spectacled Eider, and Snowy Owls. Gotta love that...But I don’t have anything against racking up a big trip list, either.

My answers are getting too long. How about some simple questions that don’t require me to think too much?

B: OK, before we finish up, maybe you could tell us your favorite thing about being a birding guide?

JP: The vicarious excitement of tour participants getting lifers and experiencing new things, but that isn’t unique to being a guide -- from my experience, just about every birder enjoys helping someone else find a bird. Getting to travel more than I would otherwise is another job benefit. I know you asked for just one thing but I’m giving you two.

That was my real world answer. My fantasy world answer would be something like this: Children running up and wanting me to autograph their binocular straps, the defeated and embarrassed look on old classmates’ faces at a high school reunion when they find out I’m a birding guide and they’re just brain surgeons and astronauts, all the attention from the ladies, and of course the money. That’s my fantasy world answer!

B: What advice might you give to potential tour participants about choosing the best tour for them?

JP: Wings (the tour company, not the band) has an essay on their website that has just about all the advice anyone would need, so even though I’m directing your readers to a competitor’s website, my advice would be to read that essay. The only additional advice would be to check with the tour operator to see when you’re expected to wake up in the morning. Not everyone enjoys getting up at o-dark-thirty.

B: And to get us out of here, gazing into your crystal ball, what new or upcoming trends do you see in birding and bird touring?

JP: Before I answer that, I want to say that if you’re not part of any trends, it doesn’t mean you’re a substandard birder. I don’t want to give the impression that you have to be part of a trend to be “with it”, and what we think of as birding will remain 98% unchanged, just as it has been since shotguns were traded in for field glasses. Also, these trends will be felt most by those of us for whom birding is a lifestyle (e.g., anyone reading your blog). With that said...

There will be an acceleration of the instant access to information that began in the early- to mid-90s due to wider use of and improvements in smartphone-type mobile devices, but it doesn’t take a crystal ball to see that coming since listservs already have real-time updates coming in from iPhones and Blackberries.

Soon no one will be complaining about a field guide being too big to carry in the field because with color e-book readers and iPads we’ll be able to carry a birding library on one small device.

Birders will take advantage of their mobile devices and cameras with audio recording capability to make more sound recordings. This will eventually lead to less fear of any Red Crossbill splits.

One trend I hope to see in the next two years is a resurgent ABA. For that to happen, I think they need to start broadening their focus and also make the internet work for them instead of against them as it has been. For example, they could create members-only wiki site guides and convert their membership directory into a Facebook-like website. I wrote a lot more on that subject on my blog. You may want to check it out if you’re having trouble sleeping. Another thing I hope to see is a book about Guy McCaskie and/or the 1970s California birding scene.

In the realm of bird tours, I think multi-day pelagic trips will grow somewhat, and some “new” destinations, both within the ABA Area and worldwide, will become more popular. I could go into some of that in more detail, but I don’t want to beat you over the head with the self-promotion. ;)

Looking further into the future, mobile devices will be able to take a picture of a bird and identify it, leading us to debate if that’s really “birding” or not. While we’re arguing about that, our machines will become self-aware, realize human birders are unnecessary, and attempt to exterminate us all. After that, a certain someone in Arizona will finally complete his guide to flycatchers, something I’ve been waiting for since 1997.

B: Thanks John, hope to be out birding with you again soon, and not just visiting here on the interwebs. Best of luck on Attu--may all your trips be filled and first North American records abound!

JP: Thank you, Birdchaser!

Monday, October 18, 2010

Evolution of the Bird Photo Field Guide, Take 2

A couple years ago I charted the rise of the bird photo field guide. Since then, several new photo field guides have come out, including the Stokes guide that is out this month, and the photographic field guides of Paul Sterry and Brian Small that came out last year. And everyone is waiting to see Richard Crossley's field guide scheduled to come out next year.

A couple years ago I charted the rise of the bird photo field guide. Since then, several new photo field guides have come out, including the Stokes guide that is out this month, and the photographic field guides of Paul Sterry and Brian Small that came out last year. And everyone is waiting to see Richard Crossley's field guide scheduled to come out next year.In this review I want to focus on the Sterry & Small guides to emphasize what I think are the biggest problems with photo field guides. But first some things things that stand out about these twin Eastern and Western guides.

A) Large photos: Photos in these guides are generally generously sized--which is good in that they provide a nice look at the birds, but may be bad in that they take up so much room that we don't get as many photos of each species. The beautiful photos, most by Brian Small, are easily the best feature of these guides.

A) Large photos: Photos in these guides are generally generously sized--which is good in that they provide a nice look at the birds, but may be bad in that they take up so much room that we don't get as many photos of each species. The beautiful photos, most by Brian Small, are easily the best feature of these guides.B) Non-square format: One of my pet peeves about photo field guides is that each page becomes a series of rectangle bird images. Sterry & Small break that up by editing the photos so that the birds break through the frame of the rectangle. At one level this is great so as to get rid of the boxiness of the guide. But in some cases it becomes a bit distracting, and makes it so that the eye doesn't quickly comprehend the species on the page and their relationship to each other, and one has to pay extra attention to the labeling to make sure which image goes with each species. My initial thoughts on this were "nice layout" but after more closer review, the layout is maybe more distracting than useful--even if it looks nicer.

C) No migration on maps: I think we've all come to expect seeing migratory pathways rendered on field guide maps. These guides don't have them, so birders in most of the country would not be able to use this book to determine which migratory species might occur in their area during passage.

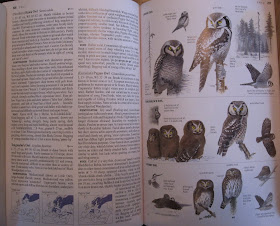

And now for some more difficult comments. To facilitate this, I'd like to compare one typical two page spread with a similar spread from what I recently called the best field guide ever, Birds of Europe, 2nd Edition (like these Sterry & Small guides, also put out in the US by Princeton Press).

Birds of Europe, 2nd Edition

Sterry & Small (Western) Photographic Guide

First things to notice:

1) Fewer bird images: 16 bird images in the illustrated guide, only 4 in the photo guide. This seems to be a fairly consistent issue with photo guides--while an artist can cram images together in an aesthetic way, that is tough if not impossible to do to the same extent in a standard photo guide.

2) Fewer plumages depicted: This goes along with the first point. Note there are no juvenile birds depicted in the photo guide. In the case of these Sterry & Small guides, there seem to be huge gaps between what is covered here and in standard field guides. When was the last time we didn't get to see juvenile Northern Saw-Whet Owls in a field guide?

3) Photos don't show as much: Despite the claim that photos show birds more realistically than illustrations, photo field guides almost always fall down on this point--they just don't show what is really needed for us to see in order to make a good identification. Read the descriptions of a bird in any photo field guide, then look at the included photos and ask if you can really see that point in the photos. More often than the authors would care to admit, the feature just isn't visible in the photo.

Here are some examples from just this owl page--look closely to see if you can see these features mentioned in the text:

Northern Hawk-Owl

--"Long-tailed appearance is diagnostic" (maybe not too obvious in photo)

--"Gray-brown overall" (we only see under parts, not most of dorsal side)

--"Upperparts are marked with pale spots..." (again, we only see a little of the upperparts)

--"...smallest and densest on the head" (you can see this, but only on the crown)

--"Underparts are barred..." (thank you, yes that is visible)

--"as is the long, tapered tail" (tail hardly visible at all)

--"Eyes and bill are yellow and facial disc is pale and rounded..." (yes)

--"...with striking white eye-brows" (OK, its there, but photos of other owls on page have at least as striking eye-brows, so what's the point of the mention?)

Northern Saw-Whet Owl

OK view of back as described, but can't really see the "underparts whitish, but heavily streaked rufous." Again, juvenile not shown at all.

Boreal Owl

--"Rich brown plumage overall" (not visible)

--"Upperparts are marked with bold white spots, smallest and densest on head" (not really visible.

--"Underparts are whitish, but heavily streaked with rufous brown" (OK, but looks more dark brown than rufous in photos)

--"Facial disc is whitish with dark border (OK)

--"Yellow eyes" (eyes are mostly closed)

--"...framed by white eyebrows" (OK I guess, but not most distinctive feature.

That's not a great percentage of mentioned features readily visible in the photos.

4) "Extra photos": In this format, there are often "extra" photos over on the left-hand side within the text of the species accounts. Usually, more photos is better, but often in this guide the photos seem more attractive than useful. Case in point the Bristle-thighed Curlew illustration on the curlew page (above). Nice to have the bird illustrated, but just as with the owl page, most of the identifying features listed for the species are not visible in the photo at all.

5) Missing flight shots: This could just be another subset of the above categories, but for most birds we aren't given photos of the birds in flight. And sometimes when they are, they can cause problems, such as...

6) Photo artifacts create confusion: Case in point, the Great Egret shot on page 87 of the Western guide (p. 77 in the Eastern) seems to show the bird with black underwings. Experienced birders will know that this is a photographic artifact due to lighting, but a beginner could be easily mislead. Just another point that photos just don't always show the birds in the best way for them to be identified.

7) Distracting backgrounds: Great thing about an illustrated guide is that the birds can be depicted against a uniform background--usually white or another pale color to best show off the plumage. In photo guides, each bird is vignetted with what are usually just distracting background leaves or other features, making the eye and mind work harder to get a clear image of the bird itself. In illustrated guides, backgrounds can be shown that are actually useful, such as the numerous small image shots of birds in the Birds of Europe that illustrate interesting behaviors or habitat features.

8) Clutter: Sometimes the guide succumbs to the temptation to pack in too many images in too small a space, such as pp.158-159 in the Western Guide, where 12 variously sized photos of Western Gull, Sabine's Gull, and Black-legged Kittiwake are so crowded as to be distracting.

9) Poor Comparisons: That same crowded gull plate illustrates another problem--because of the nature of fitting photographs onto the pages, you rarely get good close images of two similar species in proximity to each other. A standard of illustrated field guides is to depict similar species right next to each other to facilitate easy comparison. You just can't do that as well with photos. On the crowded gull plate, there is no reason to have Western Gull next to these smaller species--it would be better served in close proximity to some of the other larger gulls.

Granted, many of the problems with these guides are shared by other photo field guides, so in some cases I am just pointing out the limitations of this genre.

However, when it comes to the text, there are plenty of other frustrating things to puzzle about. I'll just mention the biggest problem--

Similar species: For the most part, and I think this is the book's fatal flaw, the book just doesn't tell us how to identify birds from others that may be similar. This is really bad in tough ID cases--like Empidonax flycatchers--as precious little is given here for those birds. There is no similar species section (except when there are extra-limital or range-limited similar species not covered by their own species account), and the text for most species usually doesn't mention other similar birds at all. When distinguishing features are mentioned, they are often not visible on the photos (see point #3 above). So birders are left to try and photo match what they see with one of the photos in the book, really can't use this to reliably identify more than just the most distinctive birds.

On books I like a lot, I usually list all the great things about it, then may have to mention a few problems or things I don't care for at the end. In this case, sadly, I'm left at the end of the review having spilled a lot of ink without dishing out many praises. But there are a few things that I liked that I can draw attention to in these books. The photos, despite not being the most useful for identification purposes, are by and large excellent and beautiful. This may well be the "most lavishly illustrated photographic guide" to North American birds as plugged on the back jacket. I also liked the "observation tips" section at the end of each species account. Sometimes there is fun or useful information there, such as when we are told for the Northern Hawk-Owl that "Low density, nomadic habits, and fickle site faithfulness make it tricky to pin down. However, on the plus side, diurnal habits and fondness for perching on treetops allow supurb views if you do find one." Of course, as with the other features of this book, sometimes this section is less than useful, as when it says that a species is "easy to see" or in the case of the American Golden-Plover when it states that the birds are "most reliably found by visiting Arctic breeding grounds in summer." What? Sorry, not useful for most of us!

Which is probably what I have to say in conclusion about these books. In many ways they are beautiful, but probably not useful for most of us.

Other online reviews:

10,000 Birds

Birdfreak

The Birder's Library